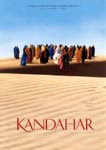

Time magazine selected Makhmalbaf’s Kandahar as one of the top 100 films of all time. If one judges quality of cinema solely by the story or the plot, Time magazine is not off the mark. It won minor awards at the Cannes and Thessaloniki film festivals as well.

Afghanistan, like Darfur (Sudan), would make any sensitive human being wince on viewing on screen the tragedy of a great nation buffeted by forces that do not get weaker but stronger each year. Generations of Afghans have faced hunger, fear and a life deprived of democracy, equality and education and, last but not least, economic and social progress. Take the Afghan factor out of the movie (something quite unthinkable!) and the film would be no better than a clever documentary. This remark does not indicate that I do not admire Mohsen Makhmalbaf as a creative filmmaker; I sincerely do.

Mr Makhmalbaf loves Afghanistan. He makes any viewer of Kandahar empathize with the problems of that country. Women of Afghanistan have less freedom than women elsewhere. They are forced to cover their bodies in a gown called the burqa and have to apply lipstick within the confines of the gown—one of the many tragi-comic details the director provides the viewer. Grown-up women have to be led by young male kids, because a male kid has more social power than a female. Children grow up in constant fear of land mines that can take away a limb and have to enrol in schools (madrasas) where education is centred on learning the Koran by rote and the importance of Kalashnikovs. Any journey to the countryside is fraught with many dangers: robbers, well-water contaminated by worms that could make one sick if consumed without boiling, check-posts governed by the Taliban that deprive you of any books that they suspect to be socially subversive. The film is definitely a great attempt by Mr Makhmalbaf to introduce the travails of the ordinary Afghan to the wider world.

An amazing visual sequence in the film presents a group of men running on crutches to grab artificial limbs dropped by low-flying aircraft near a Red Cross Centre that tries to help the growing numbers of victims of the myriad landmines. While the problem is a real one, the sequence would make any intelligent viewer wonder at the fine line dividing reality and illusion. Look closely and you will find the Afghans are caught on camera smiling when they are supposed to be running desperately to procure a prosthetic leg! There is another sequence where the director underscores the need for constant medical care for the average Afghan and that lack of proper medical care. To the credit of the director, the problem of treating a sick woman with a curtain separating the patient and doctor drives home the tragedy, however comic and unreal the scenario appears to the viewer. Somewhere in the periphery of the plot is a woman about to commit suicide. The Afghan tragedy, in spite of the unwitting comedy in the movie, is endless. Mr Makhmalbaf is not the only individual in his family concerned with the Afghan problem; his young daughter Hana made a beautiful film Buddha collapsed out of shame also on the Afghan tragedy where the historical Bamyan statues of Buddha were destroyed by the Taliban and how young girls in Afghanistan are deprived of education that young boys can access. Hana’s elder sister has made another evocative tale called Blackboards, another true scenario near the Iran/Iraq Kurdish border, where teachers literally carry blackboards to impart education to children and earn a living. The Makhmalbaf family is truly an amazing family of filmmakers from Iran.

If you want to see the creative genius of the Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf and head of this family, one needs to view his earlier but lesser known work Gabbeh, which I consider to be very close to magical cinema of the Armenian maestro Sergei Paradjanov. Gabbeh did not have rely on the subject to prove Makhmalbaf’s abilities, it transported you to the breathtaking world of cinema by the inherent merit of its visuals and sound. Here was a tale of love and lovers with the magic of Iranian carpets for a backdrop. (Incidentally, Mohsen Makhmalbaf won the Paradjanov award for cinema, a few years ago for his contribution to cinema).

Mohsen Makhmalbaf made yet another amazing film in Tajikistan called Sex and Philosophy years after he made Kandahar, where he once again showed his real talent that we glimpsed in Gabbeh. That film, unlike the suggestive title, has neither sex nor nudity—the subject of sex is merely suggested by a male hand and a female hand caressing each other, in lyrical synchrony to the violin of Vanessa Mae. The director states on his website that the four women shown are his vision of the development of the adult women. The story is constructed on a series of intellectual debates of a cynical male philosopher and his women friends, eventually retracting from the world of a lover to one of self imposed loneliness (shades of the Iranian Mehrjui's The Pear Tree and Allan Sillitoe's short story The loneliness of the long-distance runner hover, as the subject balances social concerns and politics without making either one obvious) while paying tribute to Russian literary geniuses Chekov and Tolstoy (whose names are thrown by the shopkeeper who sell three antique watches). Do not miss out the hidden, mischievous comment that the third watch on sale, indirectly connected to Stalin, is picked up by the protagonist's third lover who likes to erase the protagonist from her memory, preferring the watch to the ones related to literary figures! The film tries to imitate the colour coding of the late Polish genius Kieslowski. In this Makhmalbaf film, the four women wear black, red, blue and white and the colour coding is accomplished quite well. Evidently the second lover had shades of the last of the four characters as she wears one red shoe and one white one. The switch from one colour to the other is gradual.

The film is very well made with touches of the absurd (talking to each other within the same car using mobile phones, "a cold coffee with a cold smile", a poodle in a woman's bed preferred to the human lover) and the surreal (a big passenger plane with just one passenger, autumn leaves covering a dance hall, the lighted candles on the dashboard of a moving car, etc).

To revert to Makhmalbaf’s Kandahar, I applaud the director’s intentions. The colour of the bridal party of burqa clad women looks lovely. With the same breath, I wonder if those colourful burqas can be associated with Taliban ruled Afghanistan where black and grey are often the colour of burqas that one would tend to associate lifestyles of Afghan women in the remote parts of the country. But then this is Mr Makhmalbaf of the colourful Gabbeh and Sex and Philosophy as well. In any case, whether you loved Kandahar or not, it would make you reflect on what it showed. As an Indian national, I loved the Sanskrit shlokas being recited on the soundtrack from time to time. Was Mohsen Makhmalbaf trying to be ecumenical? Or was it his family's love for Indian culture that made this addition?

But if you want to see the director at his best—I recommend Gabbeh or his later film Sex and Philosophy. The moot question is what do you want in good cinema: do you want the subject or do you want an intelligent presentation of the subject to overpower your senses? Mr Makhmalbaf can present both types of cinema in separate films that he has made.

P.S. Hana Makhmalbaf's Buddha Collapsed from Shame was reviewed earlier on this blog.

Excellent article Thank you very much

ReplyDeleteAwesome post. Really like this post. "Safar e Gandehar" contain something special & unique theme.

ReplyDelete