Ostensibly Kieslowski chose white of the French flag to make a movie on equality. Equality if it can be reached in marriage, makes it work. Marriage is rocked when an equilibrium is not reached. A dove can be caressed and be a symbol of peace and purity; a dove can defecate and dirty as well

White in the movie is used as an epiphany of the joyous moments in marriage. The doves are weaved in Kieslowski visually and aurally to accentuate the marriage as a rite of passage in life. He brings in the phrase "light at the end of the tunnel" towards the end of the film. There is another marriage, that of Mikolaj in the subplot that also survives in a strange way.

The film begins with divorce proceedings and ends with the wife signalling the reinstatement of the wedding ring on her finger. The film begins with husband recalling the wedding that has failed. The doves flying overhead unload excreta on him. Towards the end of the film, the husband again recalls the wedding as he sets off for the wife's prison.

Kieslowski's treatise on equality is based on marriage as a great leveller with the doves flutter captured on the soundtrack appearing as a frequent reminder of marital bonds. It even appears in the underground metro, an unlikely place if you have a logical mind. You have to throw away logic if you need to enjoy this film.

There are aspects of the film that are obviously unrealistic. Putting a grown man in a suitcase and letting the suitcase go through airport security is not feasible. Moreover, the director shows the heavy suitcase perched precariously on a luggage cart. Impossible to believe all these details.

But the deeper question is whether Kieslowski was using marriage as a metaphor for politics? There is the mention of the Russian corpse with the head crushed for sale, there is a mention of the neon sign that sputters...The name Karol Karol seems reminiscent of Kafka.

Sex in this film is not to be taken at face value. Impotence of Karol Karol at strategic points of the film is deceptive. He apparently does more than hair care for women clients at his hair care parlor in Poland (suggested, not shown). I have a great admiration for Polish cinema, having gown up watching works of Wajda and Zanussi. I met Kieslowski in 1982 when he attended an international film festival in Bangalore, India, promoting his film Camera Buff, another film with Jerzy Stuhr, who plays Jurek in White. I took note of Camera Buff but I could not imagine the director of Camera Buff would evolve into a perfectionist a decade later. Stuhr has been metamorphosed from a live wire in Camera Buff to an effeminate colleague of Karol Karol in White. White is a carefully made work with support of other top Polish directors in the wings--Zanussi and Agniezka Holland.

Although the film is heavy in symbolism, it is also a parody. Karol Karol comes to kill with a blank bullet and a real one. Did he plan that out, when he did not know who he was going to shoot?

The performances are all brilliant--the good Polish, Hungarian, and Czech filmmakers extract performances from their actors that could humble Hollywood directors, because the stars are not the actors but the directors. Great music. Great photography. And a very intelligent script.

This is a major film of the Nineties--providing superb wholesome entertainment and food for thought. It is sad for the world of cinema that Kieslowski passed away.

A selection of intelligent cinema from around the world that entertains and provokes a mature viewer to reflect on what the viewer saw, long after the film ends--extending the entertainment value

Friday, September 22, 2006

Thursday, September 21, 2006

14. The late Italian director Sergio Leone's US masterpiece "Once Upon a Time in America" (1984): A great swansong

Not many realize that Sergio Leone was offered the chance to direct Puzo's The Godfather but opted to make Once Upon a Time in America. They say he regretted this decision later in life--but it would be pertinent to know why someone like Leone would have made such a decision.

Any Leone fan would know the importance the director gives to music, structure of the story, the importance of money and how it corrupts many values. All these elements are underlined in this gangster film. In Coppola's work, the story afforded more importance to social details, character details and fabulous camera-work. Both works are monumental--but I preferred Leone's work, truncated to less than 4 hours than his original cut of 6 hours.

The music. Leone's favorite Ennio Morricone provided one of the finest film music for this film and he won awards for this film as he had won praise for Leone's The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly and a host of other spaghetti westerns by Leone. But the real contributor of music was a Romanian flute player called Georghe Zamfir who plays the brilliant, haunting Pan's song just as Zamfir played the same tune equally effectively in Australian Peter Weir's Picnic at Hanging Rock made 9 years before Leone's film. Weir and Leone both know their music and both need to be complimented for picking up this obscure Romanian to enhance their films. Leone's cinema does not limit to brilliance of music--he uses sound to give effects that surpass the camera eye. The ringing telephone--a telephone ring that persists before the number dial moves on the instrument--provided a stamp of Leone that no viewer will easily forget--and no director had accomplished so effectively. Of course, the telephone call was so central to the film's plot. If the telephone was not enough, the sound of the lift moving up (without a passenger) plays another aural reminder of Leone's cleverness behind the camera.

The structure. Leone's screenplay of switching from the present to the past and vice versa increases the entertainment value. Coppola's work was linear and less demanding of the viewer. In many ways Leone's work comes very close to the Coppola's third Godfather film--his least appreciated Godfather film, which mixes pathos, irony and closure to intrigues. Leone's film is many ways quite philosophical as was Coppola's Godfather III--far removed from the brutal and power-hungry Godfather I and II. Leone was able to add a dash of comedy--scenes with antics of the Artful Dodger in Carol Reed's Oliver! are copied in the sequences of the early years. Leone's comedy can span from a simple act of hungry boy eating a cream pastry that he had bought to impress his love interest to a young girl taunting her boy lover that "his mother is calling" when his male friend whistles. Coppola's cinema rarely dealt with comedy, unless it was a precursor to tragedy. Several sequences where Leone switches time--the eyes of the protagonist changing from the old to the young man, the appearance of the protagonist in the railway station, and the Frisbee hitting the protagonist as he walks the lonely cold street--makes the film more exciting and colorful. The long film is suddenly less boring as it entertains you while unfolding the saga. The switching of the female child with the male, the corruption among the law enforcers, and the obvious dwarfing of the female characters against the male parts for Leone appears more pronounced than in Coppola, because the intent is to underline the weakness of male folly at the height of their power.

The film is Leone's essay on American's interest in getting rich and powerful at the cost of simple values of honor and friendship. At the end the director emphasizes the importance of honor and friendship even among gangsters and even women who often ultimately seek the rich guy to live with rather than the true lover.

The effect of De Niro's final laugh at the camera can be interpreted in several ways. Who is he laughing at? The camera? The audience? The irony of his life? Is the chase for money worth it? It reminds me of Richard Burton's character, a vicious bank robber, who in the final shot of the remarkable British film Villain (1971) turns around at the camera and shouts "Who do you think you are looking at?"

Leone could not have made Godfather I or II, but he could have dealt with Godfather III. And Coppola could never have made Once upon a time in America. Leone's decision to change the name of the film from the novel's name The Hoods gives an indication of where the director is leading the audience.

The more you see the film you realize the film is a robust one that will stand the test of time because Leone did not want to merely present an interesting saga on screen but entertain intelligently.

Any Leone fan would know the importance the director gives to music, structure of the story, the importance of money and how it corrupts many values. All these elements are underlined in this gangster film. In Coppola's work, the story afforded more importance to social details, character details and fabulous camera-work. Both works are monumental--but I preferred Leone's work, truncated to less than 4 hours than his original cut of 6 hours.

The music. Leone's favorite Ennio Morricone provided one of the finest film music for this film and he won awards for this film as he had won praise for Leone's The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly and a host of other spaghetti westerns by Leone. But the real contributor of music was a Romanian flute player called Georghe Zamfir who plays the brilliant, haunting Pan's song just as Zamfir played the same tune equally effectively in Australian Peter Weir's Picnic at Hanging Rock made 9 years before Leone's film. Weir and Leone both know their music and both need to be complimented for picking up this obscure Romanian to enhance their films. Leone's cinema does not limit to brilliance of music--he uses sound to give effects that surpass the camera eye. The ringing telephone--a telephone ring that persists before the number dial moves on the instrument--provided a stamp of Leone that no viewer will easily forget--and no director had accomplished so effectively. Of course, the telephone call was so central to the film's plot. If the telephone was not enough, the sound of the lift moving up (without a passenger) plays another aural reminder of Leone's cleverness behind the camera.

The structure. Leone's screenplay of switching from the present to the past and vice versa increases the entertainment value. Coppola's work was linear and less demanding of the viewer. In many ways Leone's work comes very close to the Coppola's third Godfather film--his least appreciated Godfather film, which mixes pathos, irony and closure to intrigues. Leone's film is many ways quite philosophical as was Coppola's Godfather III--far removed from the brutal and power-hungry Godfather I and II. Leone was able to add a dash of comedy--scenes with antics of the Artful Dodger in Carol Reed's Oliver! are copied in the sequences of the early years. Leone's comedy can span from a simple act of hungry boy eating a cream pastry that he had bought to impress his love interest to a young girl taunting her boy lover that "his mother is calling" when his male friend whistles. Coppola's cinema rarely dealt with comedy, unless it was a precursor to tragedy. Several sequences where Leone switches time--the eyes of the protagonist changing from the old to the young man, the appearance of the protagonist in the railway station, and the Frisbee hitting the protagonist as he walks the lonely cold street--makes the film more exciting and colorful. The long film is suddenly less boring as it entertains you while unfolding the saga. The switching of the female child with the male, the corruption among the law enforcers, and the obvious dwarfing of the female characters against the male parts for Leone appears more pronounced than in Coppola, because the intent is to underline the weakness of male folly at the height of their power.

The film is Leone's essay on American's interest in getting rich and powerful at the cost of simple values of honor and friendship. At the end the director emphasizes the importance of honor and friendship even among gangsters and even women who often ultimately seek the rich guy to live with rather than the true lover.

The effect of De Niro's final laugh at the camera can be interpreted in several ways. Who is he laughing at? The camera? The audience? The irony of his life? Is the chase for money worth it? It reminds me of Richard Burton's character, a vicious bank robber, who in the final shot of the remarkable British film Villain (1971) turns around at the camera and shouts "Who do you think you are looking at?"

Leone could not have made Godfather I or II, but he could have dealt with Godfather III. And Coppola could never have made Once upon a time in America. Leone's decision to change the name of the film from the novel's name The Hoods gives an indication of where the director is leading the audience.

The more you see the film you realize the film is a robust one that will stand the test of time because Leone did not want to merely present an interesting saga on screen but entertain intelligently.

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

13. German director Wim Wender's US film "The Million Dollar Hotel" (2000): Stamp of a mature director

Here's an American film made with a European touch that provides social, psychological and political commentary. The story was conceived and the music provided by Bono (of U-2 fame). U-2, incidentally, provided the music for many of Wim Wender's recent films.

I watched this Wim Wenders film, 25 years after I last saw a film by this German director. I have only seen two others Kings of the Road and The Wrong Movement both made in the mid-Seventies. Wim Wenders impressed me then, he impresses me now. He is a social commentator who loves to deal with alienated individuals. He is a German who loves Americana, its varied hues of lifestyles and contrasting views of life.

The opening helicopter shot caressing the sleek LA skyscrapers well clad in glass and steel ends up with the skeleton of the Million Dollar Hotel neon sign. In the background an airplane is taking off. Those who recall Kings of the Road will remember a similar scene in a lonely landscape.

The film is not a mystery film. It is more a reflective, surrealist, social commentary. The first shot of the Mel Gibson FBI character is from his shoes only gradually revealing the man in the shoes. The man in the shoes is a modern Don Quixote, patched up by medical technology. No one in the film is real--each character is unreal with element of realism. Each statement of the script is loaded with social comment. Example "you have to vote in a democracy with a Y or a N, a Y for why and N for why not.." Everyone is manipulating everyone: the media moghul the media, the FBI the suspects, the denizens of hotel each other, the hotel owner his guests, the music business the musicians..If you are attentive the film is hilarious in its wacky social commentary. It reminded me of the fine Danny Kaye (his last regular movie) film The Mad Woman Of Chaillot directed by Bryan Forbes and based on Jean Giradoux' play, where the characters are equally farcical, while the social commentary is sharp as a knife.

Wim Wenders in America is different from Wenders in Europe. He uses American clichés but his cinema remains European. That Gibson contributed his role without pay underlines Gibson's respect for Wenders. Wenders belongs to the era of German cinema (the Seventies) that spewed many talented filmmakers: Syberberg, Fassbinder, von Trotta, Schlondorff, Herzog and Hauff. That this film's true content and value are lost on many Americans is a social comment that must have amused Wenders. Wenders has not withered, he is as effective as he was in his prime, combining strong scripts with fascinating images and marrying both with good music.

See the movie and let the allegories sink in--a hotel that hosts mentally challenged people, too poor to afford medical insurance. If you can figure out the allegories, the movie is a treasure trove.

I watched this Wim Wenders film, 25 years after I last saw a film by this German director. I have only seen two others Kings of the Road and The Wrong Movement both made in the mid-Seventies. Wim Wenders impressed me then, he impresses me now. He is a social commentator who loves to deal with alienated individuals. He is a German who loves Americana, its varied hues of lifestyles and contrasting views of life.

The opening helicopter shot caressing the sleek LA skyscrapers well clad in glass and steel ends up with the skeleton of the Million Dollar Hotel neon sign. In the background an airplane is taking off. Those who recall Kings of the Road will remember a similar scene in a lonely landscape.

The film is not a mystery film. It is more a reflective, surrealist, social commentary. The first shot of the Mel Gibson FBI character is from his shoes only gradually revealing the man in the shoes. The man in the shoes is a modern Don Quixote, patched up by medical technology. No one in the film is real--each character is unreal with element of realism. Each statement of the script is loaded with social comment. Example "you have to vote in a democracy with a Y or a N, a Y for why and N for why not.." Everyone is manipulating everyone: the media moghul the media, the FBI the suspects, the denizens of hotel each other, the hotel owner his guests, the music business the musicians..If you are attentive the film is hilarious in its wacky social commentary. It reminded me of the fine Danny Kaye (his last regular movie) film The Mad Woman Of Chaillot directed by Bryan Forbes and based on Jean Giradoux' play, where the characters are equally farcical, while the social commentary is sharp as a knife.

Wim Wenders in America is different from Wenders in Europe. He uses American clichés but his cinema remains European. That Gibson contributed his role without pay underlines Gibson's respect for Wenders. Wenders belongs to the era of German cinema (the Seventies) that spewed many talented filmmakers: Syberberg, Fassbinder, von Trotta, Schlondorff, Herzog and Hauff. That this film's true content and value are lost on many Americans is a social comment that must have amused Wenders. Wenders has not withered, he is as effective as he was in his prime, combining strong scripts with fascinating images and marrying both with good music.

See the movie and let the allegories sink in--a hotel that hosts mentally challenged people, too poor to afford medical insurance. If you can figure out the allegories, the movie is a treasure trove.

Sunday, September 17, 2006

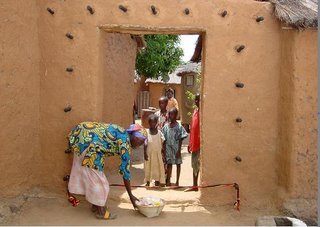

12. Senegalese director Ousmane Sembene's "Moolaade" (2004): Africa ought to be proud of this film!

Ousmane Sembene is a colossus among African filmmakers. He is what Kurosawa and Ray are to Asia. At 82, this man is making films on women's problems, on colonialism, on human rights without losing sight of African culture.

Moolaade deals with rebellion by African women against female circumcision, a tradition upheld by elders, Muslim and animist, in a swathe of countries across Saharan and sub-Saharan Africa. Interestingly, the film is an uprising within the social traditions that allow the husband full powers over his wives and acceptance of other social codes to whip his wife in public into submission. How many women (and feminist) directors who preach about female emancipation would have dared to make a film on this subject in Africa? The subject could cause riots in countries such as Egypt. Sembene is more feminist than women and I admire this veteran for this and other films he has made. He graphically shows how women are deprived of sexual pleasures through this practice and how thousands die during the crude operation.

Moolaade deals with other aspects of Africa as well. It comments on the adherence to traditional values that are good--six women get protection through a code word and piece of cloth tied in front of the entrance to the house. It comments on materialism (including a bread vendor with a good heart for the oppressed who is called a "mercenary" by the women who claim to know the meaning of the word) that pervades pristine African villages (the return of a native from Europe and the increasing dependence on radios for entertainment and information).

Sembene's cinema is not stylish--its style stems from its simplicity and its humane values. Sembene's films allow non-Africans to get inside the world of the real Africa far removed from the world of the Mandelas, constant hunger and the epidemic of AIDS that the media underlines as Africa today. Sembene's film is not history, it is Africa today. The performances are as close to reality as you could get.

At the end of the film shown at the 2005 Dubai Film Festival, I could not but marvel at a man concerned not at making great cinema for arts' sake but using it creatively to improve the human condition of a slice of humanity the world (and the media) prefers to ignore. How many of us worry about the conditions of life in Africa, let alone the social problems of women in Africa? Here is a director nudging us to think on those lines. Through this film, a subject that most Muslims prefer not to discuss is brought to the screen.

Saturday, September 16, 2006

11. Valerie Guignabodet's French film "Mariages!" (2004): Weaving entertainment from strands of reality

The film is an essay on marriages. Robert Altman tried to do the same in A Wedding and ended up with a delectably visual and aural feast that missed your heart by a mile. Altman tried to approach the subject as a black comedy, while this French film reaches out truthfully to lay bare all the charades between man and woman as seen through the lives of different married couples over a couple of days. Altman is a man; Valerie Guignabodet is a woman--viva la difference! Guignabodet unlike Altman is not worried about the ceremony; Guignabodet is more interested in dissecting the cadaver as in an autopsy. In the end, her final shot of the bride's mother walking away taking the middle path (literally and figuratively) away from it all is a masterstroke. The end, in some ways, is better than the rest of the film because it makes a mute statement. (Remember the comparable end of Mazursky's An Unmarried Woman?)

The rest of the film belongs to the actors--the most underrated actress in the world Miou-Miou (see her in Claude Miller's Dites-lui que je l'aime or that brilliant Netoyages a sec) and the arresting Mathilde Seigner. True they have great lines but they make the characters leap out the screen, however small (a teeny weeny Air France seat TV screen in my case).

The film is unusual--it has sex but never visually shown. The film captures the effect on other characters in the movie. The social jibes at the British (thru a fictional Kenneth Branagh who never appears) and the East Europeans (a Pole who is seen as Russian) could easily have been an Altman effect, but director Guignabodet is able hit you below the belt as she makes jabs after jabs at various social institutions, e.g., replacing the wedding march music with pathos, the best man who forgets the rings, traditional marriages compared to modern ones, role of gays vs. heterosexuals at marriages. A true blue-blooded French film, if ever there was one. The French do know the art of leaving the viewer to reflect on insitutions other nationalities take for granted. This is a fine example where the debate begins in the mind of the viewer as the film spool runs out.

P.S. Not many films titles have exclamation marks at the end. Therein hangs a tale!

The rest of the film belongs to the actors--the most underrated actress in the world Miou-Miou (see her in Claude Miller's Dites-lui que je l'aime or that brilliant Netoyages a sec) and the arresting Mathilde Seigner. True they have great lines but they make the characters leap out the screen, however small (a teeny weeny Air France seat TV screen in my case).

The film is unusual--it has sex but never visually shown. The film captures the effect on other characters in the movie. The social jibes at the British (thru a fictional Kenneth Branagh who never appears) and the East Europeans (a Pole who is seen as Russian) could easily have been an Altman effect, but director Guignabodet is able hit you below the belt as she makes jabs after jabs at various social institutions, e.g., replacing the wedding march music with pathos, the best man who forgets the rings, traditional marriages compared to modern ones, role of gays vs. heterosexuals at marriages. A true blue-blooded French film, if ever there was one. The French do know the art of leaving the viewer to reflect on insitutions other nationalities take for granted. This is a fine example where the debate begins in the mind of the viewer as the film spool runs out.

P.S. Not many films titles have exclamation marks at the end. Therein hangs a tale!

Thursday, September 14, 2006

10. Aki Kaurismaki's Finnish film "Mies vailla menneisyytta" (2002) (A Man Without a Past)--Reducing the world into a man, a woman, a dog and trains

This movie is deceptive--a casual viewing could discard it as another "feel good" film from Europe.

It permeates Christian values without sermons, priests, or any religious hard sell (a small poster of Christ in a booth of the Salvation Army is an exception). Philosophically, it presents Tabula Rasa or a clean slate to begin life anew. The film tends to be absurdist (not even a moan emanates from brutalized victims of violence, broken noses are twisted back painlessly, victims of violence emerge from shadows to mete out justice). The film recalls shades of the brilliance of Tomas Alea's early Cuban films and the humanity of Zoltan Fabri's Hungarian cinema.

The film presents entertainment of a kind that would be alien to Hollywood--a cinematic essay on human values that seem to be a rare commodity the world over. There is no sex; there is no need for it. The poor who live in garbage bins and in empty containers, are rich with pockets full of kindness, helping each other without any expectation of a reward. The rich and powerful (the ex-wife and her lover, the policemen, the hospital staff, the official who rents out illegal living space) seem bereft of true feelings or any human kindness. The poorer sections of society (the electrician, the restaurant staff, the family who nurses the main character, the Salvation Army staff) do good to others, care about others and expect nothing in return.

The film is an affirmation of Christian values without preaching religion. The main female character in love with the man, is ready to sacrifice her love because she genuinely respects marriage vows and even brings a "train" schedule to send off her lover to his wife. The art of giving is sanctified. A man who employed workers believes in paying his workers, even if it meant robbing a bank to do so. A lawyer argues a case well because he likes the Salvation Army. Symbolically, even half a potato among six or eight harvested is given away to some stranger wanting to eat it and avoid scurvy! Again, symbolically there is rain on a clear day to help grow the few potatoes...

The film provides humour of a quaint, Finnish variety. A timid dog that eats leftover peas is called Hannibal--a male name one can associate with a king or even the cannibalistic Hannibal Lecter--even though the dog is female. There are swipes taken against the government and its associated machinery (antiquated laws, North Korean buying Finnish banks, retirement benefits, strikes and strikers, bank staff, corrupt banking practices).

Trains play a crucial role in Kaurismaki's screenplay. It begins and ends the film. It also punctuates the film, when the past is revealed, briefly.

There are possible flaws in the film--the blue tint when the children spot the injured man. The unexplained Japanese dinner with Sake and Japanese music on the train. The significance of the cigar in the script is elusive. The choice of songs, however good, seem to be haphazard.

The script is otherwise brilliant. In glorifying the detritus of society, Kaurismaki seems to affirm there is indeed a link between the tree and falling dead leaf (with reference to a comment by a character in the movie). The train moves on. Forward, not backwards!

Minimizing the world into a man, a woman, a dog and trains, Kaurismaki serves a feast of observations for a sensitive mind--a tale told with a positive approach to move on and seize the day. It is a political film, an avant garde film, a comedy and a religious film, all lovingly bundled together by a marvelous cast.

Finland should thank Kaurismaki--he is her best ambassador. He makes the viewer love the Finns, warts and all!

It permeates Christian values without sermons, priests, or any religious hard sell (a small poster of Christ in a booth of the Salvation Army is an exception). Philosophically, it presents Tabula Rasa or a clean slate to begin life anew. The film tends to be absurdist (not even a moan emanates from brutalized victims of violence, broken noses are twisted back painlessly, victims of violence emerge from shadows to mete out justice). The film recalls shades of the brilliance of Tomas Alea's early Cuban films and the humanity of Zoltan Fabri's Hungarian cinema.

The film presents entertainment of a kind that would be alien to Hollywood--a cinematic essay on human values that seem to be a rare commodity the world over. There is no sex; there is no need for it. The poor who live in garbage bins and in empty containers, are rich with pockets full of kindness, helping each other without any expectation of a reward. The rich and powerful (the ex-wife and her lover, the policemen, the hospital staff, the official who rents out illegal living space) seem bereft of true feelings or any human kindness. The poorer sections of society (the electrician, the restaurant staff, the family who nurses the main character, the Salvation Army staff) do good to others, care about others and expect nothing in return.

The film is an affirmation of Christian values without preaching religion. The main female character in love with the man, is ready to sacrifice her love because she genuinely respects marriage vows and even brings a "train" schedule to send off her lover to his wife. The art of giving is sanctified. A man who employed workers believes in paying his workers, even if it meant robbing a bank to do so. A lawyer argues a case well because he likes the Salvation Army. Symbolically, even half a potato among six or eight harvested is given away to some stranger wanting to eat it and avoid scurvy! Again, symbolically there is rain on a clear day to help grow the few potatoes...

The film provides humour of a quaint, Finnish variety. A timid dog that eats leftover peas is called Hannibal--a male name one can associate with a king or even the cannibalistic Hannibal Lecter--even though the dog is female. There are swipes taken against the government and its associated machinery (antiquated laws, North Korean buying Finnish banks, retirement benefits, strikes and strikers, bank staff, corrupt banking practices).

Trains play a crucial role in Kaurismaki's screenplay. It begins and ends the film. It also punctuates the film, when the past is revealed, briefly.

There are possible flaws in the film--the blue tint when the children spot the injured man. The unexplained Japanese dinner with Sake and Japanese music on the train. The significance of the cigar in the script is elusive. The choice of songs, however good, seem to be haphazard.

The script is otherwise brilliant. In glorifying the detritus of society, Kaurismaki seems to affirm there is indeed a link between the tree and falling dead leaf (with reference to a comment by a character in the movie). The train moves on. Forward, not backwards!

Minimizing the world into a man, a woman, a dog and trains, Kaurismaki serves a feast of observations for a sensitive mind--a tale told with a positive approach to move on and seize the day. It is a political film, an avant garde film, a comedy and a religious film, all lovingly bundled together by a marvelous cast.

Finland should thank Kaurismaki--he is her best ambassador. He makes the viewer love the Finns, warts and all!

Labels:

Cannes winner

,

Finland

,

Flanders winner

,

San Sebastian winner

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

9. Paolo Sorrentino's Italian film "Le conseguenze dell'amore" (Consequences of Love) (2004)--Laugh and then reflect on why you laughed

I saw this interesting film back to back with the Chinese/French film 2046 at the 2005 Dubai Film festival. Both were intelligent works made the same year (2004/2005). Both had the main characters living in a "hotel". In both films, the hotel is more a metaphor of exile than a location. Both dealt with love between a man and a woman. Both had wonderful music and riveting performances. What a coincidence and yet how the two films differ in treatment of the subject!

Somewhere at the beginning of the film, a man walking on a pavement turns to look at a woman and in doing so hits a lamp post. The audience erupts in a volcano of laughter quite innocently. But isn't that brief shot the synopsis of the film, that entertains you for 2 hours? While the film is a wonderful blend of black comedy (e.g., using a stethoscope to listen to a neighbor's conversation in the adjoining hotel room), the film builds on what Buster Keaton and Jacques Tati had introduced to cinema earlier--stoic faces that leads to comedy quite in contrast to the equally intelligent world of Robin Williams or the heartwarming Danny Kaye. The sudden frenzy of activity of an otherwise stoic character moving money from the hotel to the bank is reminiscent of Tati's works and recently reprized in Zvyagintsev's Elena.

But the film is not mere comedy. The anti-automation statement (cash counting and the reaction of the bank staff to the statements relating to it, the dummy that acts as an ineffectual warning to the speeding lady, the reference to "Moulimix" as the fictitious "company" he works for, etc.) are several cues that the director is offering a loaded comedy to the viewer. Laugh, yes, but reflect on it and enjoy further...

The movie's strength lies in is brief, staccato script (by director Paul Sorrentino) that offers comedy that is mixed with philosophy ("Truth is boring," "Dad is dead, but nobody told him," "Bad luck does not exist--it is the invention of the losers and the poor". Then the director goes on to provide you with a fascinating lecture from the main character on insomniacs. You will not sleep through this lecture.

There is a loaded philosophical sequence where a young girl, sitting opposite the lead character Titta Di Girolamo, reads aloud a passage from a book: "Whatever he wants can happen. What a fine mess. That is the advantage of using memories to excite oneself. You can own memories, you can buy even more beautiful ones. But life is more complicated, human life especially so, a frightening, desperate adventure. Compared to this life of formal perfectionism, cocaine is nothing but a stationmaster’s pastime. Let us return to Sophie.. We become poetic as we admire her being, beautiful and reckless, the rhythm of her life flowed from different springs than ours. Ours can only creep along, envious. This force of happiness both exciting and sweet, that animated her, disturbed us. It unsettled us in an enchanting way, but it unsettled us nevertheless. That’s the word.” The reaction of Titta to the passage is interesting. Titta is himself a cocaine addict. Titta looks at the barmaid of the hotel-his own "formal perfectionism." The following sequence is of Titta calling his own wife and daughter on the phone--a conversation filled more with silence than words. They, too, are Titta's "memories." The final sequence of the film is of Tittas' best friend Dino Guiffre working alone repairing a fault on an electricity pylon in biting wind and a snowy landscape--recalling his own best friend Titta. This is a film about friendship that transcends the mafia.

Sorrentino provides entertainment pegged to the subject the Italians know best--the Mafia. It is an existential mafia film.

Since "Truth is boring", the director provides a dessert as part of the fine meal of superb acting (Toni Servillo), good music, clever camera-work (Luca Bigazzi), a beautiful, enigmatic actress (Magnani, grand-daughter of the immortal, striking Anna Magnani) and a powerful script. The dessert is for the viewer to figure out the truthful feelings of Titta, towards his family members, towards his hotel guests, towards the bar girl, towards the mafia, towards the bankers, towards the hotel owner, and towards his best friend Dino. (Assuming that the viewer accepts the eventuality of how Titta recovered his suitcase from the goons, how does he get inside his car and get it covered with its synthetic cover while he is still inside it?) Perhaps it is Sorrentino's admitted love for the literary works of Louis-Ferdinand Céline that has sculpted the character of Titta. The film's end will remain an enigmatic one for a reflective viewer.

P.S. Consequences of Love is one of the author's top 15 films of the 21st Century. Subsequent works of the director, This Must be the Place (2011), The Great Beauty (2013), and Youth (2015) have been reviewed on this blog.

8. Changwei Gu's Chinese film "Kong que" (Peacock) made in 2005--A gorgeous family epic that makes the audience positively review their lives

When accomplished cinematographers take to direction, they often make superb films (William Fraker's Monte Walsh, Nicholas Roeg's Don't Look Now and Govind Nihalani's Aakrosh, are examples) that are often widely accepted as monumental movies much later. In the case of cinematographer-turned-director Changwei Gu, to be awarded a Silver Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival for his debut as a director must have been nothing short of a dream start into a new career.

Interestingly Chinese director Gu, opted to entrust the camera to Shu Yang and not do the job the world knew him to be accomplished at. Director Gu, however, opts to act as a lonely, blind accordion player who commits suicide.

I am not Chinese but this film had me enraptured from start to finish. The film had superb music by Peng Dou (courtesy Chinese National Symphony Orchestra), enchanting photography, incredible performances and a multi-layered story of a close-knit five member family with family values best appreciated in Asian communities. Though the film is set in the late Seventies following the years of the Cultural Revolution, the film is almost devoid of direct political comments.

The film is a common man's epic. The film is a 144 minute film (originally 4 hours) that was easily the most rewarding film at the 2005 Dubai Film Festival. It is a tale of a 5 member family told in three segments by the three children: a daughter who causes trouble for the family but emerges from an ugly duckling into a mature and cynical swan; an elder son who is mentally challenged, physically bloated, but pure in heart; and a younger son, loving, sensitive and occasionally worldly wise. The three perspectives of the family are punctuated by a cardinal shot of the family eating a simple meal. Like Kurosawa's Rashomon, the three versions offering different perspectives of the family provide cinematic entertainment that is demanding of the viewer.

The first segment of the story from the view of the girl is richer than the other two, primarily due to the rich musical subplot of her interactions with the blind musician (played by the director). The segment offers fodder for the impressionable dreamer in all of us: the power and the glory associated with a parachutist soldier, the importance of getting married to a loving husband, and the importance of playing music very well as an escape route from the daily social drudgery of washing bottles.

The second segment told from the perspective of the mentally challenged brother looks at society and predictable collective reactions to simple incidents that are not based on reason or analysis.

The third segment told from the practical younger brother's view takes another perspective--the best way to survive in an evolving society that is neither one of a dreamer or one of submission to mass reaction.

The film ends with three families of the sister and two brothers passing a peacock in a zoo. They state the peacock never dances in the winter. As they move on, the peacock does dance. The beauty of life is best perceived as you move away from the incidents and look at it from a distance, dispassionately. Melodrama takes a back seat. In the forefront, the director presents a philosophical, positive view of life--not in the least limited to the geographical boundaries of China.

I wish more people get to see this gorgeous family epic from China. It is one of the finest films of the decade. See this movie and you will truly re-evaluate your life positively.

Monday, September 04, 2006

7. Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieslowski's Dekalog 5 (Dekalog, piec) (1988) -- a disturbing treatise on killing

The brilliant Polish director--whom I had the good fortune to meet in Bangalore at an International Film Festival in 1982--made a series of ten 1-hour long short films, each dedicated to one of the Ten Commandments, handed down to Moses from God. These are commandments given to a man venerated by Christians, Muslims and Jews. Dekalog 5 naturally deals with the Fifth Commandment--"Thou shall not kill." Kieslowski and his co-scriptwriter Krzysztof Piesiewicz weave a modern day story that entertains, while asking disturbing and provoking questions--theological, social and psychological--of the viewer.

Three distinct and distant individuals' lives intersect with the brutal killing of one by another. The one-hour film only reveals the event that brings the three individuals together only after half the film is over. I have seen other segments of the Dekalog but this one struck me as the most sparse one in dialogue and yet most fascinating in structure.

The film opens with a law student practicing a mock plea of defense for a man charged with murder. Obviously the same arguments must have been repeated by the man as a full-fledged lawyer but this is never shown on screen (at least in the short 1-hr version of Dekalog 5). We are made to imagine that this must have been the case. A cab driver who is a misanthrope, has two facets to his character: the good side feeds a mangy dog, cleans his cab meticulously, picks up dirty rags thrown by people who lack civic sense, and remembers his wife while dying; the bad side frightens small poodles, refuses to give a ride to a drunk--probably worried that he will puke in the cab--and ogles at pretty girls. The repulsive protagonist who murders without mercy, drops stones from bridges on fast moving traffic, and pushes strangers into urinals without any provocation, is also a person who can make innocent young girls laugh. Kieslowski's film and the script thus present the good and the bad side of two of the three main characters.

Yet the film is not about capital punishment but more a treatise on killing. The Fifth Commandment "Thou shalt not kill" is explored theologically--("Even God spared Cain...'), sociologically the tenderness of brutes to children and poor forlorn dogs, and psychologically (after effects of drunken night with a male friend that led to the accidental death of his sister, whose photograph he carries with him). What makes ordinary persons turn into killers--this is never fully explained but suggestions are legion.

In Kieslowski's world there is a pattern where events and people are interlinked in a cosmic sense (note the resemblance of clown to the killer, as it hangs from the mirror in the cab). Kieslowski and the young idealist lawyer seem to ask us to look at the Commandment literally and figuratively--why do we kill? Are the people legally killed truly bad? Is there a force beyond society (the drunken night that led to life of a girl) that makes us into abhorrent murderers?

It would be missing the forest for the trees to discuss the two detailed killings in the film--both without mercy. The film invites the viewer to contemplate why we are asked by God not to kill.

I understand a longer full-length version of the film was made by Kieslowski. But even this short 1-hr version is superb with its bleak and sparse script, intelligent editing, interesting cinematography and top-notch direction that provides much more than the sum of its parts.

This segment anticipates the more wholesome Dekalogs 6,7 and 8. The ten films that constitute Dekalog, for me, remains one of finest cinematic achievements in the history of movies.

P.S. Detailed reviews of Dekalog's segments 2 and 5 are posted on this blog by the author.

Three distinct and distant individuals' lives intersect with the brutal killing of one by another. The one-hour film only reveals the event that brings the three individuals together only after half the film is over. I have seen other segments of the Dekalog but this one struck me as the most sparse one in dialogue and yet most fascinating in structure.

The film opens with a law student practicing a mock plea of defense for a man charged with murder. Obviously the same arguments must have been repeated by the man as a full-fledged lawyer but this is never shown on screen (at least in the short 1-hr version of Dekalog 5). We are made to imagine that this must have been the case. A cab driver who is a misanthrope, has two facets to his character: the good side feeds a mangy dog, cleans his cab meticulously, picks up dirty rags thrown by people who lack civic sense, and remembers his wife while dying; the bad side frightens small poodles, refuses to give a ride to a drunk--probably worried that he will puke in the cab--and ogles at pretty girls. The repulsive protagonist who murders without mercy, drops stones from bridges on fast moving traffic, and pushes strangers into urinals without any provocation, is also a person who can make innocent young girls laugh. Kieslowski's film and the script thus present the good and the bad side of two of the three main characters.

Yet the film is not about capital punishment but more a treatise on killing. The Fifth Commandment "Thou shalt not kill" is explored theologically--("Even God spared Cain...'), sociologically the tenderness of brutes to children and poor forlorn dogs, and psychologically (after effects of drunken night with a male friend that led to the accidental death of his sister, whose photograph he carries with him). What makes ordinary persons turn into killers--this is never fully explained but suggestions are legion.

In Kieslowski's world there is a pattern where events and people are interlinked in a cosmic sense (note the resemblance of clown to the killer, as it hangs from the mirror in the cab). Kieslowski and the young idealist lawyer seem to ask us to look at the Commandment literally and figuratively--why do we kill? Are the people legally killed truly bad? Is there a force beyond society (the drunken night that led to life of a girl) that makes us into abhorrent murderers?

It would be missing the forest for the trees to discuss the two detailed killings in the film--both without mercy. The film invites the viewer to contemplate why we are asked by God not to kill.

I understand a longer full-length version of the film was made by Kieslowski. But even this short 1-hr version is superb with its bleak and sparse script, intelligent editing, interesting cinematography and top-notch direction that provides much more than the sum of its parts.

This segment anticipates the more wholesome Dekalogs 6,7 and 8. The ten films that constitute Dekalog, for me, remains one of finest cinematic achievements in the history of movies.

P.S. Detailed reviews of Dekalog's segments 2 and 5 are posted on this blog by the author.

Labels:

Poland

,

San Sebastian winner

,

Venice winner

6. Arthur Penn's US film made in 1970--"Little Big Man"--an oxymoron that prepares us for tragi-comedy

`Little big' is an oxymoron. Little Big Man, the film, is another cinematic oxymoron: a tragi-comedy.

Most of Penn's movies are double-edged swords presenting serious subjects with a twinkle in the eye--The Miracle Worker seems to be an exception to the rule. Penn seem to have a strange knack of picking subjects that seem to be governed by forces greater than themselves--leading to alienated situations. My favorite Penn film is the 1975 film Night Moves which ends with the boat going round in circles in the sea.

This work of Penn and novelist Thomas Berger follows the same pattern. The main character Crabb is buffeted between the Red Indians and the whites by forces beyond his control. Only once is he able to control his destiny--to lead Custer to his doom, because Custer in his impetuosity has decided to act contrary to any advice from Crabb. The religious and social values of both seem vacuous. The priest's wife may seem religious but is not. The adopted grandfather cannot die on the hilltop but has to carry on living. The gunslinger is a cartoon. Historical heroes like Wild Bill Hickok are demystified into individuals with down-to-earth worries.

It is surprising to me that many viewers have taken the facts of the film and novel as accurate--when it is obviously a work of fiction based on history. The charm of the film is the point of view taken by the author and director. The comic strain begins from the time Jim Crabb's sister is not raped by the Indians right up to the comic last stand of Custer. The film is hilarious as it presents a quirky look at every conceivable notion presented by Hollywood cinema: the brilliant acumen of army Generals, the Red Indian satisfying several squaws, the priest's wife turned prostitute who likes to have sex twice a week but not on all days, the quack who has turned to selling buffalo hides as he sees it as a better profession even if he has lost several limbs, etc.

The film is a tragedy--a tragic presentation of the Red Indian communities decimated by a more powerful enemy, tragic soldiers led by megalomaniac Generals, heroes reduced to fallible individuals, all heroes (including the Red Indians) whittled down to dwarfs.

The film is a satire of a dwarf who claims to have achieved a great revenge on Custer, a dwarf who could not assassinate Custer, the dwarf in many of us. It is a great film, but often misunderstood. Penn is a great director, whose greatness cannot be evaluated by this one film but by the entire body of his films. What he achieved in this film outclasses films like Tonka (1958) and Soldier Blue (1970), two notable films on similar themes. Chief Dan George, Dustin Hoffman, and cinematographer Harry Stradling Jr have considerably contributed to this fine cinematic achievement, but ultimate giant behind the film is Arthur Penn.

Penn has presented yet another example of looking at a subject and seeing two sides of the coin that appear as contradictions but together enhance our entertainment.

Most of Penn's movies are double-edged swords presenting serious subjects with a twinkle in the eye--The Miracle Worker seems to be an exception to the rule. Penn seem to have a strange knack of picking subjects that seem to be governed by forces greater than themselves--leading to alienated situations. My favorite Penn film is the 1975 film Night Moves which ends with the boat going round in circles in the sea.

This work of Penn and novelist Thomas Berger follows the same pattern. The main character Crabb is buffeted between the Red Indians and the whites by forces beyond his control. Only once is he able to control his destiny--to lead Custer to his doom, because Custer in his impetuosity has decided to act contrary to any advice from Crabb. The religious and social values of both seem vacuous. The priest's wife may seem religious but is not. The adopted grandfather cannot die on the hilltop but has to carry on living. The gunslinger is a cartoon. Historical heroes like Wild Bill Hickok are demystified into individuals with down-to-earth worries.

It is surprising to me that many viewers have taken the facts of the film and novel as accurate--when it is obviously a work of fiction based on history. The charm of the film is the point of view taken by the author and director. The comic strain begins from the time Jim Crabb's sister is not raped by the Indians right up to the comic last stand of Custer. The film is hilarious as it presents a quirky look at every conceivable notion presented by Hollywood cinema: the brilliant acumen of army Generals, the Red Indian satisfying several squaws, the priest's wife turned prostitute who likes to have sex twice a week but not on all days, the quack who has turned to selling buffalo hides as he sees it as a better profession even if he has lost several limbs, etc.

The film is a tragedy--a tragic presentation of the Red Indian communities decimated by a more powerful enemy, tragic soldiers led by megalomaniac Generals, heroes reduced to fallible individuals, all heroes (including the Red Indians) whittled down to dwarfs.

The film is a satire of a dwarf who claims to have achieved a great revenge on Custer, a dwarf who could not assassinate Custer, the dwarf in many of us. It is a great film, but often misunderstood. Penn is a great director, whose greatness cannot be evaluated by this one film but by the entire body of his films. What he achieved in this film outclasses films like Tonka (1958) and Soldier Blue (1970), two notable films on similar themes. Chief Dan George, Dustin Hoffman, and cinematographer Harry Stradling Jr have considerably contributed to this fine cinematic achievement, but ultimate giant behind the film is Arthur Penn.

Penn has presented yet another example of looking at a subject and seeing two sides of the coin that appear as contradictions but together enhance our entertainment.

Sunday, September 03, 2006

5. An impressive debut from Argentina--"Hermanas" (Sisters) (2005)--intelligent and intellectual

Director Julia Solomonof has shown viewers that she can present a work that has an assured pace of a structured thriller while presenting a film that is basically a character study of two sisters reacting differently under the Argentinan dictatorship and reign of terror in 1970. She has learned the craft from working with Walter Salles on The Motorcycle Diaries as an assistant director.

I saw this Spanish/Argentinan/Brazilian co-production at the 2005 Dubai International Film Festival and was bowled over by the competence of the director and the performances of the actors especially that of the young boy interacting with his aunt.

The film reminded me in many ways of Hungarian director Zoltan Fabri's 1976 film The Fifth Seal (Az otodik pecset), a film set in Hungary under Nazi occupation, where friends crack under fear and pressure. Fabri apparently worked on a wonderful Hungarian novel of the same name by Ferenc Santa, which I long to read in English. In that Hungarian film, freedom and dignity of five individuals are tested under torture. Hermanas extends the similar options available to all of us under extreme conditions.

Hermanas looks at how an individual can place priorities on saving a near one from torture, while others look at the moral responsibility beyond the immediate kith and kin. The film leaves you disturbed: does the family matter more than a larger community? Even philosophers will find this disturbing to answer--which is why the late Fabri related the question to the opening of the Fifth Seal (the Martyr's seal-those who laid down their lives for the Word of God) in the Book of Revelations, the final book in the Bible.

Julia Solomonof has proved her mettle. Though I am physically far removed from Argentina, Spain or Brazil, I will watch out for her next directorial effort with anticipation.

I saw this Spanish/Argentinan/Brazilian co-production at the 2005 Dubai International Film Festival and was bowled over by the competence of the director and the performances of the actors especially that of the young boy interacting with his aunt.

The film reminded me in many ways of Hungarian director Zoltan Fabri's 1976 film The Fifth Seal (Az otodik pecset), a film set in Hungary under Nazi occupation, where friends crack under fear and pressure. Fabri apparently worked on a wonderful Hungarian novel of the same name by Ferenc Santa, which I long to read in English. In that Hungarian film, freedom and dignity of five individuals are tested under torture. Hermanas extends the similar options available to all of us under extreme conditions.

Hermanas looks at how an individual can place priorities on saving a near one from torture, while others look at the moral responsibility beyond the immediate kith and kin. The film leaves you disturbed: does the family matter more than a larger community? Even philosophers will find this disturbing to answer--which is why the late Fabri related the question to the opening of the Fifth Seal (the Martyr's seal-those who laid down their lives for the Word of God) in the Book of Revelations, the final book in the Bible.

Julia Solomonof has proved her mettle. Though I am physically far removed from Argentina, Spain or Brazil, I will watch out for her next directorial effort with anticipation.

4. Iranian director Mohsen Amiryousefi's debut film in Farsi/Persian language--"Khab-e talkh" (Bitter Dreams) (2004): A brilliant mockumentary

Bitter dreams is an unforgettable debut by 32 year-old Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Amiryousefi, who first took to mathematics as a career and then to film-making. The film won the grand prize at the Thessaloniki Film Festival, Greece. I caught up with the film and its filmmaker at the Dubai Film Festival. The film has only been screened twice within Iran, according to the director, but has been shown at Cannes, Thessaloniki and Dubai film festivals.

The film is a black comedy filmed in a pseudo-documentary style--probably better known as "mockumentary." The film revolves around a handful of individuals who run the rough equivalent of an undertakers establishment in a small town in Iran. The dead are washed, cleaned and buried covered with a special cloth by certain individuals. For female corpses, there is a lady to do the needful. A grave is dug by the grave digger. All the other clothes, ornaments, dentures, watches, jewelry are supposed to be burnt by another individual. The financial payments of the activities are divided by the chief of the cemetery, Esfandiar, and a portion of the profits go the local cleric.

|

| Touches of Hamlet's gravedigger |

The director does not document these activities in the traditional way a documentary film would. Instead he chooses to use the documentary film technique in an unusual way to film fiction. He uses real locations, real workers of the graveyard, and a pseudo-TV interview technique of questions and answers. Sometimes you only hear the questions, sometimes only the answers--you are forced to guess what you have not heard. Sometimes both questions and answers are heard.

Half-way into the film, "the recordings" take a life of their own on the TV of Esfandiar, the sullen bodywasher, who looks after the graveyard. The TV acts as a source of information to Esfandiar on what the others working with him think of him. The TV set appears to suggest that Ezrael, the Angel of Death is coming for him. The TV set allows Esfandiar to have a "dialog" with modern day undertakers in Iran's cities. It allows him (and the viewer of the film) to compare the historical variants of dealing with the dead (the ancient Egyptians, the skulls that remind you of Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge, etc.). The director allows the black and white TV to switch off and on on its own. Is it Esfandiar's inner self? Is it his alter ego? This is a unique technique in cinema--reminding you of Stanley Kubrick's HAL the computer in 2001--A Space Odyssey.

Was Amiryousefi influenced by any director, I asked, after the screening? None, he asserted, to me. He is probably truthful as his film-making is indeed unusual. There are times when you are reminded of the late Cuban filmmaker Tomas Alea's Death of a Bureaucrat. The mathematician in Amiryousefi surfaces--he lets Esfandiar describe the numeral "5" as the pregnant woman and "9" as the old man, obviously referring to the visual imagery of the number.

There are several indirect references to Shakespeare's gravedigger in Hamlet--talk of a girl committing suicide after falling in love with someone, a quibble on "to be or not to be", and the production of a skull from the grave being dug.

The "bitter dream" of preparing for the time when death's angel knocks on your door has been worked on by many directors worldwide. Ingmar Bergman distinguished himself on the subject with The Seventh Seal. But unlike the serious Bergman, Amiryousefi looks at the universal eventuality with humor--black humor. You can enter heaven, if all those you harmed in life forgave you. If you are clever in life, you can buy forgiveness from those you had hurt in the past. Typical of current Iranian cinema, there is no sex, no profanity, only black humor with a hint of satire. Is life all about death? Does Ezrael sound like Israel, or is it our socio-political awareness reading too much into the film? Why does Esfandiar interfere in courtship of two grown up individuals--he chooses to interfere from afar with binoculars--not from the mountain top. He knows well he is loser in love (he is single, unmarried and childless) and in life, but wants to win in death and reach heaven.

|

| Of graves and those who prepare the dead for internment: visual metaphors abound |

This is unusual, brilliant, and path-breaking low budget ("no-budget" according to the director) cinema that hopefully will be seen by many in Iran and elsewhere. Iranian cinema is indeed on the march this decade.

P.S. This film is on the author's top 100 films list and the author's top 15 films of the 21st century.

Labels:

Cannes winner

,

Iran

,

Mar del Plata winner

,

Thessaloniki winner

Friday, September 01, 2006

3. Mohamed Asli's debut feature from Morocco "Al Malaika la tuhaliq fi al-dar albayda" (2004)

This is one of the finest Arab films, set in the Berber community of Morocco, evoking neo-realist images--a superb debut. The English title: In Casablanca, angels don't fly.

This is one of the finest Arab films, set in the Berber community of Morocco, evoking neo-realist images--a superb debut. The English title: In Casablanca, angels don't fly.This is a rare gem. A deceptively simple film with uncharacteristically fine production values (for an Arab film) in editing, direction and performances. It evokes memories of de Sica's Bicycle Thief, Kurosawa's Dersu Uzala, Tavianni brothers Padre Padrone and Ermanno Olmi's The Tree of Wooden Clogs. I stumbled on this considerably unsung film at the Dubai international film festival.

At a simplistic level, the film is about the travails of urban migration. Three pipe-dreams of three workers in a busy Casablanca restaurant interweave the screenplay--one dreams of a better, richer family life, one dreams of caring for his steed, and one dreams of wearing an expensive pair of shoes.

But Moroccan director Mohamed Asli presents a debut effort that would put weather-beaten directors to shame. He presents tragi-comedy that comes alive with brilliant sound editing (Raimodo Aeillo and Mauro Lazaro) as he cuts from a suicidal jump in a dream to a neighing, prancing horse; inventive camera-work (director Asli and cameraman Roberto Meddi) utilizing a camera placed on a roof of a bus weaving through Casablanca traffic behind a sack of bread destined as feed for a horse miles away in quick-motion; evocative performances by non-professional actors who slide through heavy road traffic like ballet dancers with a tray full of beverages and snacks; and the quixotic efforts of a simple man to keep his new pair of shoes clean and safe.

These are not unreal dreams. Every urban migrant has similar dreams. But Asli presents a canvas that goes beyond the obvious. Through his characters he rattles the viewer as he contrasts humanism (a stranger's helping hand to someone in shock) against capitalist insensitivity (a restaurant owner who only looks at ways to prosper disregarding the lives of his workers). There is an equally disturbing question: are you more afraid of Allah (God) or of the police? The film presents the joy of birth and pathos of death--the final sequence of dead corpse being hauled against a barren, cold, lonely landscape presents a fascinating counter-point to the opening scene of a pregnant woman surrounded by people climbing stairs to talk to her husband through an intermediary. In life and in death, things remain unattainable (ability to talk to her husband versus a dream to provide a better life for the family).

The film is set in Morocco--the film could have been set anywhere. The aura is Muslim and Arab--but the sensibility is universal. There is tragedy, there is comedy. That is the real stuff of life. Thank you, Mr Asli. I look forward to even better films from you and sincerely hope more people see and enjoy this work.

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)