This is an unusual film of exceptional values--75 minutes long in color, with hardly any spoken dialogs. I saw this Iranian film in Farsi without English subtitles at the Early Iranian cinema retrospective at the recent International Film Festival of Kerala, India. That I was watching a print without subtitles did not make a difference as there were very few lines of spoken dialogs.

This is a very accessible film for any audience to enjoy--its story and values are not merely Iranian; it's universal.

The film is set in rural Iran that had not tasted petro-dollar prosperity. The setting is on fringes of desert land, where water is scarce, rainfall scanty and hardly any blade of grass is green. Add to it wind and dust that buffets and whips man and animal and you can imagine plight of the people who live on the fringes of society.

The film is moving tale of a young teenager returning to his village with a goat--only to find his family and villagers have moved on to escape natures vagaries and that one old man remains. He gives the goat to him and goes in search of his family. Water is scarce and well water it treated with reverence and never wasted. The boy is infuriated when he sees the water being used to cool the engine of a truck. A toddler is left behind by some family that cannot tend it. The boy takes care of the child but finds it tough going and asks other families to take care. Nobody wants another mouth to feed. A bucket of water left by the boy is more useful for passing families than the child. Finally, the child is picked up by one large family and the boy is happy.

He is so caring that he saves two fishes that would have died without water by throwing them in the well. He trudges on surviving on a watermelon left behind by someone.

The boy tries to get some water for a person who was accidentally buried under sand but there is no water in the well. He digs another but there is no water. He is tired and prays for water. He digs again at another site, wishing that the dead fishes that appear in his dream can survive. Metaphorically the earth opens up and a sea of water gushes out to strains of Beethoven's 5th symphony.

If the Iranian government publicizes such works of artistic merit, Iran would be better appreciated elsewhere. The film won a top award at the Nantes Film Festival.

P.S. Amir Naderi's earlier neo-realist work The Runner (1985) has been reviewed on this blog.

A selection of intelligent cinema from around the world that entertains and provokes a mature viewer to reflect on what the viewer saw, long after the film ends--extending the entertainment value

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

Saturday, December 16, 2006

28. Mexican film "El Violin" (2005) by director Francisco Vargas: Riveting debut performance by an elderly actor and impressive photography

Imagine that you look like a grandfather in real life. Imagine that your right palm has been amputated but you play a violin with a bow strapped to the maimed arm. Imagine a director wanting to use you as a lead actor in a feature film. Imagine you win a Cannes Film Festival Best Actor prize for the Un Certain Regard section of the festival for the role. It's not a dream--it happened to Mexican actor Don Angel Tavira in the Mexican film El Violin or The Violin, directed by Francisco Vargas.

I caught up with this film at the on-going International Film Festival of Kerala, India, where it won the Silver Crow Pheasant award, the best film award bestowed on a film among the 14 competing entries by the 6200 delegates attending the festival.

I do not know how Tavira lost his palm but I learned that the director made the film keeping the future actor in mind. Tavira looks like Charles Vanel in his later years. He exudes a sincerity that touches the viewer and is not easily forgettable. He mixes sincerity with the wizened touch of an old fox.

The film is similar to Irish filmmaker Ken Loach's The wind that shakes the barley in many ways. Only The Violin is shot in black and white while Ken Loach shot his lush color. The photography is in no way amateurish. Both films are about the poor fighting mighty oppressors--in the case of El Violin poor villagers fighting a cruel Mexican army.

Finer points of the film include a marvelous dialog between grandfather and grandson that speaks highly of the director screenplay writer's Vargas' writing capability. Yet he has only made four films.

As one might have guessed the violin case and violin player are key to the development of the film. Music is a great leveler--the brutes and the aesthetes both appreciate good music.

Vargas choice to film in black and white is commendable. The violence and rape that launches the film is not extended into the film as other directors would have been tempted to do. Interestingly the strength of the film is that it does not show violence at later stages--something that Ken Loach could not restrain himself from. Violence for Vargas is not gratuitous--it is to provide the focal point. The rest of the violence is only for the viewer to imagine. Now that's good cinema.

This time Vargas had a great actor. Can he make equally good films without such innate talent of Don Tavira? My guess is that he can repeat this feat with others too. Vargas has an eye for talent, for good photography and a flair for good scriptwriting.

Labels:

Cannes winner

,

Mexico

,

San Sebastian winner

Wednesday, December 13, 2006

27. Canadian Sarah Polley's "Away from Her" (2006): Remarkable debut film and a superb performance by Julie Christie

Julie Christie's combination of talent, beauty and brains has enthralled me over four decades. Nearly a decade ago, her Oscar nominated performance in "Afterglow" established that she was not a spent force while playing a gracefully aging wife of a handyman in the US. One thought that would be her best turn at geriatric impersonations.

Less than a decade later, Christie comes up with an even better performance of a woman coping with Alzheimer's disease in a debut directorial effort Away from Her of Canadian actress Sarah Polley. I saw the film yesterday at the ongoing International Film Festival of Kerala, India, where Ms Christie, serving on the jury for the competition section, introduced her film thus: "It is immaterial whether you are rich or poor--we cannot predict what can happen to us. Enjoy the film with this thought." Ms Christie probably put in her best effort because the young director considers Ms Christie to be her "adoptive" mother, having worked together on three significant movie projects in five years. The film's subject brings memories of two similar films: Pierre Granier-Deferre' film Le Chat that won a Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival for both Jean Gabin and Simone Signoret in 1971 and Paul Mazursky's Harry and Tonto which won an Oscar for the lead actor Art Carney in 1974. This performance of Julie Christie ranks alongside those winners.

Today geriatric care is a growing problem. This film is a sensitive look at parting of married couples when one of them needs institutional care. Ms Polley's choice of the actor Gordon Pinsent is an intelligent one as the film relies on his narration and Mr Pinsent's deep voice provides the right measure of gravitas. Olympia Dukakis is another fine actor playing a lady who has "quit quitting". So is Michael Murphy doing a long role without saying a word.

The strengths of the film are the subject, the direction, the performances and the seamless editing by the director's spouse. It is not a film that will attract young audiences who are insensitive. Yet the film has a evocative scene where a young teenager with several part of her body pierced by rings is totally amazed by the devotion of the aging husband for his wife. So in a way the film reaches out to different age groups. Though it talks about sex, it can be safe family viewing material.

Chances are that most viewers will love the film if they are interested in films that are different from "the American films that get shown in multiplexes" to quote a character in the film. More importantly this film advertises the problem of Alzheimer's disease eloquently and artistically. It prepares you for future shocks.

Monday, December 11, 2006

26. Polish film "Persona non grata" (2005): One of the finest films of Polish director Krzyzstof Zanussi

Director Krzyzstof Zanussi has made 75 distinguished films and is one of the three best filmmakers from Poland--the others being Wajda and Kieslowski (the latter only peaked towards the end of his career). I consider Persona non grata to be one of Zanussi's three best efforts--one being his structurally fascinating German TV film Wege in der Nacht ("Ways in the night" or "Nightwatch") made in 1979 and the other being Imperative made in 1982. Interestingly the first two films featured the brilliant music of Wojciech Kilar, the actor Zbigniew Zapasiewicz, and original scripts of physicist turned philosophy student Krzyzstof Zanussi.

At the elementary level, Persona non grata is about diplomats and their lives. At a more complex level, Zanussi explores the relationship between Poland and post-Glasnost Russia and the denizens of both nations. At an even more complex level, Zanussi introduces the subtle differences between the orthodox Christians and Catholics--a facet that I suspect interested both Zanussi and the late Kieslowski, both close associates. There are more Catholics in Poland while Orthodox Christians dominate Russia. Zanussi differentiates the spirituality of the two in the rich verbal sparring that the film unfolds between a Polish and a Soviet diplomat. Finally, Zanussi teases the film viewer by leading the audience to suspend disbelief in the main character. For a long while, even an astute viewer is led astray. The viewer is reduced to the level of a "persona non grata" believing initially that the film is all about a diplomat about to lose his diplomatic powers at the embassy and has become a "persona non grata." This is superb cinema, supported by Kilar's "music of the spheres." The film offers rich humor and at times a biblical sermon on a New Testament passage from 2 Corinthians 1:17 "Do I say yes, when I mean no?" However, taking the context of diplomacy, around which the film revolves, the discussion takes on a different hue. But the clever Zanussi throws light and shadows on the subjects in the film (the opening credits plays with light and shadows, too).

It is a story of love, suspicion, and principles--that go beyond mere individuals. It is a story of reconciliation. It is a film that a filmmaker can make in the evening of his career. It reminds you of works like Kurosawa's Dersu Uzala or Ermanno Olmi's Tree of Wooden Clogs. It is a work of maturity. Savor it like fine cognac!

Just as it is major work of Zanussi, I believe this to be a milestone for the music composer Kilar. Poland should be proud of Zanussi and Kilar.

The film is a veritable feast for an intelligent viewer. Great performances from three great Polish actors--Zbigniew Zapasiewicz (Zanussi's favorite), Jerzy Stuhr (Kieslowski's favorite), and Daniel Olbryschsky (Wajda's favorite) adorn the film but the most striking is the acting performance of Russian actor-director Nikita Mikhalkov, who can do a great turn as a restrained comic (for example his performance in his half-brother Mikhalkov Konchalovsky's Siberiade).

But in this film a dog plays a major actor's role within a web of friendship and distrust. So does a torn photograph--Zanussi does not seem to believe that photographs can lie.

Persona non grata could easily have been named "Suspicion". The film is an ode to friendships--friends who remain loyal, friends who are not recognized as friends at best of times but are recognized as friends when tragedy strikes, and friends who dislike being insulted even by mistake. The film was screened during the on-going 11th International Film Festival of Kerala, India.

What this film proves is that Polish cinema is alive and well! It also proves Zanussi is back at his best form.

25. Iranian director Dariush Mehrjui's "Gaav" (The Cow, 1969): Stunning in simplicity but providing fodder for thought

This is a major work of cinema. It might not be well known but this film ranks with Fellini's La Strada, De Sica's The Bicycle Thief, or Mrinal Sen's Oka Oori Katha based on Premchand's story--Coffin. Why is it a major work? A UCLA graduate makes a film far removed from Hollywood approaches to cinema in Iran during the Shah's regime. The film was made 10 years before Shah quit Iran and was promptly banned. It was smuggled out of Iran to be shown at the Venice Film Festival to win an award, even without subtitles.

The film does not require subtitles. It's visual. It's simple. The story is set in a remote Iranian village, where owning a cow for subsistence is a sign of prosperity. The barren landscape (true of a large part of Iran) reminds you of Grigory Kozintsev's film landscapes as in Korol Lir (the Russian King Lear) where the landscape becomes a character of the story.

The sudden unnatural death of the cow unsettles the village. Hassan, the owner of the cow, who nursed it as his own child, is away and would be shocked on his return. Eslam, the smartest among the villagers, devise a plan to bury the cow and not tell the poor man the truth. Hassan returns home and is soon so shocked that he loses his senses. He first imagines that the cow is still there and ultimately his sickness deteriorates as he imagines himself to be the cow, eats hay, and says "Hassan" his master will protect him from marauding Bolouris (bandits from another village). Eslam realizes that Hassan needs medical attention and decides to take him to the nearest hospital. He is dragged out like a cow. "Hassan" is beaten as an animal as he is not cooperative to the shock of some humanistic villagers. The demented Hassan, with the force of an animal breaks free, to seek his only freedom from reality--death.

The film stuns you. Forget Iran, forget the cow. Replace the scenario with any person close to his earthly possessions and what happens when that person is suddenly deprived of them and you will get inside the characters as Fellini, De Sica or Sen demonstrated in their cinema.

Every frame of the film is carefully chosen. The realism afforded by the story will grip any sensitive viewer. There is a visually arresting use of a small window in the wall of the cowshed through which the villagers watch the goings on within the cowshed. The directors use of the window serves two purposes--it gives the villagers a perspective of the cowshed and the viewer a perspective of the cowshed watchers.

The film is also a great essay on the effects of hiding truth from society and the cascading fallouts of such actions.

But there is more. Director Mehrjui affords layers of meaning to his "simplistic" cinema. There is veiled criticism of blind aspects religious rituals (Shia Islam), a critical look of stupid villagers dealing with their village idiots, the jealous neighbors, the indifferent neighbors, the village thief--all elements of life around us, not limited to a village in Iran. The political layering is not merely limited to the poverty but the politics of hiding truth and the long term effect it has on society. Ironically, there are values among the poorest of the poor--the hide of a "poisoned?" animal cannot be sold!

I was lucky to catch up with the rare screening of this film at the on-going International Film Festival of Kerala, India, that devoted a retrospective section of early Iranian cinema.

This is a film that should make Iran proud. It is truly a gift to world cinema.

P.S. The Cow is one of the author's top 100 films.

Thursday, December 07, 2006

24. US director Julie Taymor's "Titus" (1999): One of the most striking adaptations of Shakespeare on screen

Why did I like the film? I applaud any director making his or her initial film who chooses to film a complex subject like Shakespeare's least known tragedy, probably the mother of all his well-known tragic plays King Lear, Othello, Macbeth, Hamlet, and Julius Caesar that literature critics have dubbed a "problem play." It is true that each of the later Shakespeare tragedies borrowed strands from Titus Andronicus. Shakespeare staging Titus Andronicus was in a way similar to Julie Taymor's effort to film the play. Shakespeare wanted to establish his name. Some even suggest that Shakespeare did not write it but borrowed the source material. Yet no one can dispute that even in Elizabethan times, the play went down well with audiences. And Shakespeare went on to write and stage more plays. But for years the play was a problem to put on stage and it is well-known that few directors chose to stage or film it, due to its gory and dark contents.

I applaud Julie Taymor's decision to pick up the play to film. Titus, the play, is relevant today even more than it was in Elizabethan days. Titus is replayed almost each day in the Middle East, in Darfur, and till recently in former Yugoslavia, in Rwanda, and in Ireland. I am delighted that Taymor chose to rework the play mixing the past Roman glory with those of Mussolini's Italy, which underlines the relevance of the play today—irrespective of whether the conquering heroes ride horses or Rolls Royces.

I congratulate Taymor's decision to create a modern "chorus" distilled in the personality of a young boy, who plays like an adult but is "shaken and stirred" by events outside, who seems to realize as the play unfolds the importance of forgiveness, tolerance and love for all. For the Greeks and even for Shakespeare, the chorus had to be old and blind (as in Macbeth) but for Taymor it's the young who have eyes to see the dawn after the dark night.

There are more facets to the film that make the film extraordinary. Jessica Lange's Tamora presents a range of emotions—crying for pity, yelling for revenge, smiling to seduce and aroused by a kiss of her mortal foe Titus. The short kiss of the aging Titus and Tamora is a highlight of the film, the kiss between conqueror and former slave, a kiss between a queen and a demented subject—all highlighted by the facial expression of Ms Lange choreographed by Taymor. This brief shot cries for our attention, as throughout the film (and play) Titus seems to be celibate. (There is no mention of Titus's wife or lover). I thought Taymor brought out the best in Ms Lange, even exceeding her range of emotion in Frances. While Anthony Hopkins might not have enjoyed making this film, Taymor brought out his finest performance to date here in this film. It was almost like watching a mellow Richard Burton rendering the lines of the Bard. Taymor and cinematographer Luciano Tavoli, who is often arresting, are able to obtain a shot of Titus crying on the stony paths, with his face and eyes inches from the stones, signifying the lowest of the low the character has been hewn down to the terra firma.

A third commanding performance was that of Alan Cumming as Saturinus, second only to his mesmerizing role in Eyes Wide Shut as a gay front office clerk. If you reflect on the film, the casting was superb.

The only flaw in the "absurdist" treatment was the introduction of the Royal Bengal tiger—which could have been replaced by a leopard or a lioness. This I thought was taking the theater of the "absurd" too far. Perhaps Taymor wanted to glamorize Tamara to be more attractive as the tiger than any other great cat. That was one decision I thought did not work well in the movie.

The film's strengths are not restricted to the screenplay, the direction and acting. The film grips you with the music and choreographed title sequence and the overall production design. You want more. You get more, if the viewer is able to think while watching the film and think laterally. This is not Gladiator or Spartacus. It challenges the senses, beyond the gore and sex. Why do people behave as they do? Is the bias of many of us limited to race and color? These are questions that Terence Mallick asked in The Thin Red Line. To appreciate Taymor's Titus multiple viewings will help, preferably with a thinking cap. I rate this film as third best Shakespeare film ever made—the first two being the Russian black and white films Korol Lir (King Lear) and Gamlet (Hamlet) directed by Grigory Kozintsev, some 40 years ago.

Finally, like Orson Welles and Terrence Mallick, Julie Taymor appears to be little appreciated within the US but more lauded elsewhere. But that should not dampen the brilliance of this talented lady and her spouse the music composer Elliot Goldenthal.

P.S. Kozintsev's King Lear (Korol Lir) is reviewed elsewhere on this blog. Titus is one of the author's top 100 films.

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

23. British director Peter Glenville's US film "The Comedians" (1967): Relevant today as ever

While many viewers might have forgotten this film, the relevance of the subject of expatriates living in countries ruled by dictators and the recognizable traits of the four major characters in many persons we encounter in life make me recall this movie again and again.

Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, Alec Guinness, and Peter Ustinov are a heady combination but I will not remember the film for any one of their "acting" capabilities as much as the four wonderful main characters woven by Graham Greene and Peter Glenville. There is almost an unrecognizable James Earl Jones whose fabulous voice is overshadowed in this film by those of Burton and the suave Guinness.

"I have no faith in faith," rants Brown (Burton) the anti-hero of the film--a typical Greene character (compare with Greene's 'The Burnt-out case'). Cynicism is turned into comedy. The splashes of Catholic motifs made in passing reference ("defrocked priest") hark back to Burton's earlier role in The Night of the Iguana. Guinness' reference to looking like a Lawrence of Arabia recalls his own role as Prince Faisal in Lean's movie. Not having read Greene's book, I am not sure whether Greene introduced these clever details into the script to suit the actors or whether the details had previously existed in the book.

The gradual unmasking of the Major (Guinness) is a treat creatively captured by Glenville and Greene. The final speech made by Burton to his group of ragged rebels seem to have a common "comic" thread with George Clooney's speech to his soldiers towards the end of the recent Mallick's The Thin Red Line.

Ustinov's diplomat and Taylor's vulnerable diplomat's wife, who admits to her lover that he is the fourth "adventure," are both comedians--Greene's likable misfits who cannot change their destiny and are strangely reconciled to accept their inevitable end. All the four main characters are "prepared" for their destiny they have designed for themselves as a consequence of previous actions in life. The closing shot of the film is a shot of a suggestive blue sky, redeeming the foibles of the comedians on terra firma.

I admit that when I saw the film some 20 years ago, I did not appreciate the film as I do now. I was missing the forest for the trees. This film does not belong to Burton, Taylor, Guinness, Ustinov, Jones or Lillian Gish. It belongs to Greene, Glenville and the French cinematographer Henri Decae.

I do not imply that Burton was not good--but George C. Scott said one should evaluate a performance by remembering the character more than the actor. It is in that context that I remember the four main characters. Burton's kisses are different here than say in Boom or Cleopatra--only to add detail to the character. Taylor is strangely subdued only to add power to her smoldering role. Guinness' gradual unmasking is pathetic yet endearing only to add more substance to the character. Decae's camera captures details that shocks--e.g., empty drawers in desks to collect bribes, public executions of rebels watched by school kids...

I am not surprised the film was a box-office failure. I am surprised that this film, to my limited knowledge, has never been taken seriously for what it offers--a superb script, commendable acting, good direction, and some fine camerawork. These are the bricks that build great cinema!

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

22."Queimada (Burn!)" (1969): Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo's powerful political film with Marlon Brando

Queimada is a film I grew up with. I saw it for the first time in a movie theater in Kolkota, India, a year after it was made. It's a film with one of the finest scores of Ennio Morricone and an ambiguous performance by Marlon Brando--that makes you wonder if the William Walker role is merely to be viewed as that of a mercenary. In my view, this is Brando's best performance. Recently, I found out that Brando himself stated this performance was "the best acting I've ever did" during a Larry King interview on CNN. It appears that his explanation on why he considered this was cut short by King, who evidently knew little about the film or the filmmaker. And so we will never know why Brando thought this was his best performance. But I think I can guess the reasons.

I have watched Queimada several times and loved Gillo Pontecorvo's direction of the scenes at the port, which are one of my favorite sequences in cinema. Pontecorvo wanted Brando to create an evil figure of "Sir" William Walker, who was a real person though not a British knight. He was an American mercenary who even went to Indo-China. Brando apparently argued with Pontecorvo that the character instead of a clear-cut evil figure should be more ambiguous and this led to major differences between the two. On viewing the film, it is evident Brando won the argument.

Franco Solinas, the screenplay writer, was a brilliant Leftist who contributed to Pontecorvo's success on Battle of Algiers and Kapo. However, their films rankled the far Left and the far Right. Quiemada's script upset the Spanish government, and the filmmakers changed the details from a Spanish colony to a Portuguese colony. But Brando who probably was aware of the American connection of the lead character must have enjoyed the parallels of the story--knowing his personal love for the native Indian cause.

The film is a witty, cynical portrayal of colonial designs on impoverished poor. Sugar was the commodity in vogue then. A century later you could replace "sugar" with "oil." The film is replete with a brilliant speech penned by Solinas, spoken by Brando that begins by comparing the economics of having a wife versus a prostitute. He then ends the speech comparing the gains of a slave with that of hired labor. The political philosophy is unorthodox but hard hitting.

This film has a small but significant role for Italian actor Renato Salvatori. The assassination sequence with Brando and Salvatori says a lot more than what it shows. The politics of the action is more important than the event itself. If you reflect on this scene, many real life assassinations take on deeper meaning.

I have seen hundreds of political movies--but this will remain my all time favorite. The film won Pontecorvo in 1970 the best director national award in Italy. The mix of Brando, Pontecorvo, Solinas, Salvatori and Morricone is a heady cocktail that will be a great experience for any intelligent viewer.

P.S. Queimada is one the author's top 100 films.

Monday, November 06, 2006

21. US director John Ford's "7 Women" (1966): a great swansong with a twist at the end

|

| Ann Bancroft in one of her finest roles |

I wonder what feminists feel about this film. In my view, this is a fascinating look at women by a male director, an effort that can compare with two other works: Paul Mazursky's The Unmarried Woman and Muzaffar Ali's Umrao Jaan. In 7 women, strong women, weak women, lesbians, and immature girls, are contrasted with cardboard male characters that are never fully developed and are obviously no match to the array of women portrayed in the film. The men are painted so negatively that one begins to wonder if Ford thought Asian men had more brawn than brain--a strange view that has gained currency in Hollywood cinema.

I applaud Ford's decision to cast Anne Bancroft in the leading role. This is one of her strong performances. She makes even the most vapid films look elegant with her roles (Lipstick, Little Nikita, to name just two). Ford develops her role on the lines of a Western gunslinger--only there are no gunfights. The woman has a weapon: sex. That weapon can down all the bad guys faster than it takes to down Mexicans, Red Indians, rustlers, bankrobbers, et al. In 7 Women these bad men are Chinese/ Mongolian thugs. Established actresses Dame Flora Robson and Margaret Leighton are totally eclipsed by Bancroft's rivetting role.

|

| The decision |

What Ford wanted, I guess, was to stun the viewer with the ending--the twist to the gradual softening of the Bancroft in men's clothes to the Bancroft in women's clothes and the acceptance of male superiority. Most critics have found the end facile but I found the end powerful as it makes you review and reconsider all the preceding information on the lead character.

|

| The film poster connects religion and the film |

The film questions the commonly held views on religion; evidently Ford was old enough to have seen enough to choose to make this film in the evening of his life. In his films, Ford's women are as interesting as any other aspect of his cinema and this film provides ample fodder for those interested in studying that element of Ford's cinema.

However, for a 1966 film, the studio sets for the film look too artificial for the serious cinema that the film offers. Despite all the flaws, the film provides ample scope for reflection.

Monday, October 16, 2006

20. Little known US TV film director Charles Carner's "Judas" (2004): Recommended only for those who have courage to accept another viewpoint

This is a remarkable film. First, because it was made at least two years before the Gospel of Judas was unearthed in Egypt a few years ago and before the National Geographic scientifically authenticated that the document was indeed written in 300 AD or earlier, by the Gnostics and or the Orthodox Christians of Egypt. It is also well established and historically accepted now that the Four Gospels of the New Testament are not the only Gospels and that King Constantine several centuries later ruled that all other Gospels other than the four in the Bible are not acceptable because he sought the path of least controversy for the propagation and consolidation of Christianity.

What is remarkable about the film is its attempt to re-evaluate the known facts surrounding a chosen disciple of Christ—-who evidently needed a Judas to betray him so that he would be crucified and thus die on the cross to leave his mortal body. Christ picked Judas; Judas did not pick Jesus. What is equally remarkable is that the film reiterates that Jesus was very close to Judas as the intellectual among the 12 apostles. He is dejected when the Keys of Heaven are given to Peter and not to him. Some of the apostles are equally surprised at Jesus' decision to bypass the apostle who was entrusted with the financial affairs of the peripatetic group.

Further, the deaths of Jesus and Judas are interlinked chronologically as the film suggests. I applaud the scriptwriters' and the directors' decision to include the shot in the film of three apostles (?) lifting the body of the dead Judas for burial—which is in line with Christian ideology that God forgives those who repent.

Finally, if the true Christian believes Christ knew how he was going to be betrayed and by whom and even commanded Judas to go and do what he had to do, the independent decision-making capability of the greatest traitor in Christendom needs considerable reassessment. According to the Gospel of Judas, Judas was told by Jesus that he would be reviled for ages and rehabilitated and venerated later. The film also suggests a linked promise made by Jesus to Judas before the betrayal of being with him after death. The film also suggests the reason for accepting the 30 pieces of silver was related to his mothers' burial—a debatable detail never mentioned in the official Gospels.

The fact that the film was not released for 2 years after it was made shows the reluctance of the producers anticipating the reaction of Christians indoctrinated by the contents of the accepted gospels. I also noticed in the credits that the film was dedicated to a Christian priest.

Not only was the subject interesting but the portrayal of Jesus and his disciples came very close to Pier Paolo Pasolini's film Gospel According to St Mathew (which received acceptance of the Catholic Church some five decades ago) both in spirit and in the obvious lack of theatrical emotions by the actors. Jonathan Scarfe's Jesus was different from the conventional but not a bad one by any count. Here was a portrayal of Jesus as a man, who spoke like any one of us and yet commanded respect. Unlike Gibson's The Passion of the Christ that concentrates on the pain and suffering of Christ, this film reaches out intellectually to explore the politics of the day and the dynamics prevailing among the twelve apostles and Mary Magdalane. It offers food for thought. This film is strictly for those who can accept another point of view in Christianity than the accepted one. For them alone, this is recommended viewing. And for those who love the power of cinema.

Thursday, October 12, 2006

19. New Zealander Jane Campion's "The Piano" (1993): Clever film that makes you wonder

This film won the Cannes Film Festival's top honor the year it was released. It is a good film. It's a clever film. You would love it, if you don't reflect on the film too much. If you do reflect on what you saw, you will begin to re-evaluate the movie, the director Campion and finally, the screenplay writer Campion, who reworked the "Bluebeard" story.

I have seen the movie twice. I liked it the first time because it was refreshingly different, restrained in some parts, erotic to an extent, with some brilliant camerawork of Stuart Drybergh and choreography (specifically, the beach scene with Holly Hunter, Keitel and Paquin, with the overhead shot and the imaginative designs of footprints in the sand).

My second viewing had me reassessing if a viewer can be led to like a film without thinking rationally. Take the example of Paquin carrying the piano key with the written message. She takes one path, retraces it and takes another. This crucial action changes the course of the film. Why did she make that choice? Coincidence? If it was deliberate, the relationship between the child and foster father is not adequately developed. The director persuades us to notice this decision with a high angle shot. We in the audience know that Kietel's character is illiterate--but the message is finally read by someone who could read. And so the story gathers momentum.

The "quiet" strength of the film is in the character who chooses to remain mute. A finger is chopped off but there is no howl of pain, only blood, only a resignation to fate.

Despite a great performance by Hunter and impressive direction by Campion, I begin to have a nagging doubt if the audience is meant to leave their mind behind and merely indulge their senses, what they see and hear...On second viewing, the script seems more manipulative rather than virtuous. In the epilogue, what are we to make of the metal prosthetic finger--that all is healed? Or was it a convenient way to end the film?

Whether you like the film or not, the film improves our appreciation of cinema as a fascinating medium of entertainment.

Labels:

Cannes winner

,

Golden Globe winner

,

New Zealand

,

Oscar winner

Thursday, October 05, 2006

18. Italian director Guiseppe Tornatore's English/French film "La leggenda del pianista sull'oceano" (The Legend of 1900) (1998): a charming fable on celluloid

When asked by the Khaleej Times in Dubai to pick my 10 best films, I listed this movie The legend of 1900 as one of the top 10 movies made in the last 25 years in the English language. Few had seen it, thanks to poor marketing. Interestingly the movie has neither sex nor violence. It even does not even have a typical happy ending. Yet almost everyone who has seen the film heaps praise on this amazing film.

The film released in English as "The legend of 1900," is a fable of an orphan born on a transatlantic passengership on 1 Jan 1900, who is adopted by the crew and almost never leaves the ship even when the ship is to be dismantled and sold as scrap. This strange child evolves into a gifted pianist, rivalling the best alive.

It has all the facets of a soap opera but it's much more. The story is an allegory of people who choose to remain in the security of the known, and never venture into uncharted lands. The film offers much to savor beyond the obvious story. It is also a fine tale of friendship between two men, with no shred of homosexuality.

I love music; I admire the work of Ennio Morricone. I love good cinematography and the Hungarian films of cinematographer Lajos Koltai have long appealed to me. It is perhaps natural that the first film I have seen of Guiseppe Tornatore that involves Morricone and Koltai should appeal to me.

But in retrospect, the film grabbed me because the appeal of the film went beyond Morricone and Koltai. The performances of Tim Roth, Vince, Williams and Nunn were arresting. Roth's British accent at the end was annoying (who could have contributed that to 1900 when the character grew up on the ship?) but otherwise both Roth and Vince played very convincing roles. The casting is commendable--especially when some of the players are not very famous.

There were certain sequences that Koltai and Tornatore can be truly proud of: playing the rolling piano on a ship swaying to choppy seas and the engine room sequence with Nunn and the child.

Most of all, the marketing of the film as a fable, which it is, has its own charm. I particularly loved the song at the end of the film "written" by Morricone--or is it wrongly credited?-- and sung by Pink Floyd's ex-lead singer. Don't miss it as it captures the story in the song as the credits roll by.

This is a very European film, which is probably the reason it has not been given the recognition that it deserves in the US. I strongly recommend this film to many of my friends who have not seen it. Tornatore, Koltai and Morricone weave magic together.

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

17. US filmmakers Michael and Mark Polish's "Northfork" (2003): A notable effort using surreal and absurdist images offering layers of entertainment

"It all depends on how you look at it-–we are either halfway to heaven or halfway to hell," says the priest Rev. Harlan in Northfork. The Polish brothers' film is an ambitious one that will make any intelligent viewer to sit up, provided he or she has patience and basic knowledge of Christianity. The layers of entertainment the film provide takes a viewer beyond the surreal and absurd imagery that is obvious to a less obvious socio-political and theological commentary that ought to provoke a laid-back American to reflect on current social values. The film's adoption of the surreal (coffins that emerge from the depths of man-made lakes to float and disturb the living, homesteaders who nearly "crucify" their feet to wooden floor of their homes, angels who need multiple glasses to read, etc.) and absurd images (of half animals, half toys that are alive, of door bells that make most delicate of musical outputs of a harp, a blind angel who keeps writing unreadable tracts, etc.) could make a viewer unfamiliar with the surreal and absurdist traditions in literature and the arts to wonder what the movie is un-spooling as entertainment. Though European cinema has better credentials in this field, Hollywood has indeed made such films in the past —in Cat Ballou, Lee Marvin and his horse leaned against the wall to take a nap, several decades ago. Northfork, in one scene of the citizens leaving the town in cars, seemed to pay homage to the row of cars in Citizen Kane taking Kane and his wife out of Xanadu for a picnic.

The film is difficult for the uninitiated or the impatient film-goer—the most interesting epilogue (one of the finest I can recall) can be heard as a voice over towards the end of the credits. The directors seem to leave the finest moments to those who can stay with film to the end. If you have the patience you will savor the layers of the film—if you gulp or swallow what the Polish bothers dish out, you will miss out on its many flavors.

|

| Darryl Hannah in the role of the androgynous Angel |

What is the film all about? At the most obvious layer, a town is being vacated to make way for a dam and hydroelectric-project. Even cemeteries are being dug up so that the mortal remains of the dead can be moved to higher burial grounds. Real estate promoters are hawking the lakeside properties to 6 people who can evict the townsfolk. Of the 6, only one seems to have a conscience and therefore is able to order chicken broth soup, while others cannot get anything served to them.

At the next layer, you have Christianity and its interaction on the townsfolk. Most are devout Christians, but in many lurk the instinct to survive at the expense of true Christian principles, exemplified in the priest. Many want to adopt children without accepting the responsibilities associated with such actions.

At the next layer, you have the world of angels interacting with near angelic humans and with each other. You realize that the world of the unknown angel who keeps a comic book on Hercules and dreams of a mother, finds one in an androgynous angel called "Flower Hercules." While the filmmaker does give clues that Flower is an extension of the young angel's delirious imagination, subsequent actions of Flower belie this option. You are indeed in the world of angels--not gods but the pure in spirit—and therefore not in the world of the living. The softer focus of the camera is in evidence in these shots.

At another layer the toy plane of Irwin becomes a real plane carrying him and his angels to heaven 1000 miles away from Norfolk.

The final layer is the social commentary—"The country is divided into two types of people. Fords people and Chevy people." Is there a difference? They think they are different but both are consumerist.

To the religious, the film says "Pray and you shall receive" (words of Fr Harlan, quoted by Angel Flower Hercules). To the consumerist, the film says "its what we do with our wings that separate us" (each of the 6 evictors also have wings--one duck/goose feather tucked into their hat bands but their actions are different often far from angelic as suggested by the different reactions to a scratch on a car).

The film is certainly not the finest American film but it is definitely a notable path-breaking work--superb visuals, striking performances (especially Nick Nolte), and a loaded script offering several levels of entertainment for mature audiences.

Tuesday, October 03, 2006

16. US filmmakers Joel and Ethan Coen's "Blood Simple" (1984): A movie to make you laugh (and then reflect on why you laughed)

Debut films have a quality that experience smothers. What struck me first was the disarming innocence of a clever script--not a single cop surfaces in a film replete with so many killings, an Alsation makes its presence felt early in the film but disappears soon after, and a dead man (no proof that he did die, of course!) narrates the prologue of the movie. A fresh towel laid out on a car seat lets blood stain it with ferocious osmotic quality as though the towel was covering a fresh wound! But the blood is several hours old. Yet the movie is clever enough to make you think you are cleverer than those you are watching, because the directors let you, the viewer, know more than the characters themselves.

The Coen brothers are very clever. I thought O brother, where art thou to be average fare until I realized that it was based on Homer's Odyssey, which the Coen brothers deny having read. But neither have I read Homer in original but even without reading Homer a somewhat literate individual can see the obvious parallels. When you realize what they have done you do not hate the Coens but you begin to admire their ingenuity--their scripts reduce the Greek heroes to mortal escaped prisoners or simple anti-heroes.

In Blood Simple, blood that suddenly oozes from a nostril lets the viewer know more than the characters in the film. The comedy of errors that weave the film, invites the viewer to laugh at the dumb actions of each character. But then none of the characters know what the viewer knows and appear dumber than the average person.

The Coens have mastered this gift of portraying the average man or woman, simple or crooked, placed within a spartan canvas of knee-jerk emotions. You laugh. You cry. You go through catharsis. The Greeks have taught the Coens the grammar of entertainment.

Robust performances, striking camera-work (L.A. Confidential picked up several clues from this film), and interesting dialogs invite you to leave your brain behind as you laugh at "stupid" characters on the screen. You enjoy the film even further if you reflect on why you enjoyed the film.

Friday, September 22, 2006

15. Polish director Krzysztof Kieslowski's "Trzy kolory: bialy" (Three colors: white) (1994); White as a metaphor

Ostensibly Kieslowski chose white of the French flag to make a movie on equality. Equality if it can be reached in marriage, makes it work. Marriage is rocked when an equilibrium is not reached. A dove can be caressed and be a symbol of peace and purity; a dove can defecate and dirty as well

White in the movie is used as an epiphany of the joyous moments in marriage. The doves are weaved in Kieslowski visually and aurally to accentuate the marriage as a rite of passage in life. He brings in the phrase "light at the end of the tunnel" towards the end of the film. There is another marriage, that of Mikolaj in the subplot that also survives in a strange way.

The film begins with divorce proceedings and ends with the wife signalling the reinstatement of the wedding ring on her finger. The film begins with husband recalling the wedding that has failed. The doves flying overhead unload excreta on him. Towards the end of the film, the husband again recalls the wedding as he sets off for the wife's prison.

Kieslowski's treatise on equality is based on marriage as a great leveller with the doves flutter captured on the soundtrack appearing as a frequent reminder of marital bonds. It even appears in the underground metro, an unlikely place if you have a logical mind. You have to throw away logic if you need to enjoy this film.

There are aspects of the film that are obviously unrealistic. Putting a grown man in a suitcase and letting the suitcase go through airport security is not feasible. Moreover, the director shows the heavy suitcase perched precariously on a luggage cart. Impossible to believe all these details.

But the deeper question is whether Kieslowski was using marriage as a metaphor for politics? There is the mention of the Russian corpse with the head crushed for sale, there is a mention of the neon sign that sputters...The name Karol Karol seems reminiscent of Kafka.

Sex in this film is not to be taken at face value. Impotence of Karol Karol at strategic points of the film is deceptive. He apparently does more than hair care for women clients at his hair care parlor in Poland (suggested, not shown). I have a great admiration for Polish cinema, having gown up watching works of Wajda and Zanussi. I met Kieslowski in 1982 when he attended an international film festival in Bangalore, India, promoting his film Camera Buff, another film with Jerzy Stuhr, who plays Jurek in White. I took note of Camera Buff but I could not imagine the director of Camera Buff would evolve into a perfectionist a decade later. Stuhr has been metamorphosed from a live wire in Camera Buff to an effeminate colleague of Karol Karol in White. White is a carefully made work with support of other top Polish directors in the wings--Zanussi and Agniezka Holland.

Although the film is heavy in symbolism, it is also a parody. Karol Karol comes to kill with a blank bullet and a real one. Did he plan that out, when he did not know who he was going to shoot?

The performances are all brilliant--the good Polish, Hungarian, and Czech filmmakers extract performances from their actors that could humble Hollywood directors, because the stars are not the actors but the directors. Great music. Great photography. And a very intelligent script.

This is a major film of the Nineties--providing superb wholesome entertainment and food for thought. It is sad for the world of cinema that Kieslowski passed away.

White in the movie is used as an epiphany of the joyous moments in marriage. The doves are weaved in Kieslowski visually and aurally to accentuate the marriage as a rite of passage in life. He brings in the phrase "light at the end of the tunnel" towards the end of the film. There is another marriage, that of Mikolaj in the subplot that also survives in a strange way.

The film begins with divorce proceedings and ends with the wife signalling the reinstatement of the wedding ring on her finger. The film begins with husband recalling the wedding that has failed. The doves flying overhead unload excreta on him. Towards the end of the film, the husband again recalls the wedding as he sets off for the wife's prison.

Kieslowski's treatise on equality is based on marriage as a great leveller with the doves flutter captured on the soundtrack appearing as a frequent reminder of marital bonds. It even appears in the underground metro, an unlikely place if you have a logical mind. You have to throw away logic if you need to enjoy this film.

There are aspects of the film that are obviously unrealistic. Putting a grown man in a suitcase and letting the suitcase go through airport security is not feasible. Moreover, the director shows the heavy suitcase perched precariously on a luggage cart. Impossible to believe all these details.

But the deeper question is whether Kieslowski was using marriage as a metaphor for politics? There is the mention of the Russian corpse with the head crushed for sale, there is a mention of the neon sign that sputters...The name Karol Karol seems reminiscent of Kafka.

Sex in this film is not to be taken at face value. Impotence of Karol Karol at strategic points of the film is deceptive. He apparently does more than hair care for women clients at his hair care parlor in Poland (suggested, not shown). I have a great admiration for Polish cinema, having gown up watching works of Wajda and Zanussi. I met Kieslowski in 1982 when he attended an international film festival in Bangalore, India, promoting his film Camera Buff, another film with Jerzy Stuhr, who plays Jurek in White. I took note of Camera Buff but I could not imagine the director of Camera Buff would evolve into a perfectionist a decade later. Stuhr has been metamorphosed from a live wire in Camera Buff to an effeminate colleague of Karol Karol in White. White is a carefully made work with support of other top Polish directors in the wings--Zanussi and Agniezka Holland.

Although the film is heavy in symbolism, it is also a parody. Karol Karol comes to kill with a blank bullet and a real one. Did he plan that out, when he did not know who he was going to shoot?

The performances are all brilliant--the good Polish, Hungarian, and Czech filmmakers extract performances from their actors that could humble Hollywood directors, because the stars are not the actors but the directors. Great music. Great photography. And a very intelligent script.

This is a major film of the Nineties--providing superb wholesome entertainment and food for thought. It is sad for the world of cinema that Kieslowski passed away.

Thursday, September 21, 2006

14. The late Italian director Sergio Leone's US masterpiece "Once Upon a Time in America" (1984): A great swansong

Not many realize that Sergio Leone was offered the chance to direct Puzo's The Godfather but opted to make Once Upon a Time in America. They say he regretted this decision later in life--but it would be pertinent to know why someone like Leone would have made such a decision.

Any Leone fan would know the importance the director gives to music, structure of the story, the importance of money and how it corrupts many values. All these elements are underlined in this gangster film. In Coppola's work, the story afforded more importance to social details, character details and fabulous camera-work. Both works are monumental--but I preferred Leone's work, truncated to less than 4 hours than his original cut of 6 hours.

The music. Leone's favorite Ennio Morricone provided one of the finest film music for this film and he won awards for this film as he had won praise for Leone's The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly and a host of other spaghetti westerns by Leone. But the real contributor of music was a Romanian flute player called Georghe Zamfir who plays the brilliant, haunting Pan's song just as Zamfir played the same tune equally effectively in Australian Peter Weir's Picnic at Hanging Rock made 9 years before Leone's film. Weir and Leone both know their music and both need to be complimented for picking up this obscure Romanian to enhance their films. Leone's cinema does not limit to brilliance of music--he uses sound to give effects that surpass the camera eye. The ringing telephone--a telephone ring that persists before the number dial moves on the instrument--provided a stamp of Leone that no viewer will easily forget--and no director had accomplished so effectively. Of course, the telephone call was so central to the film's plot. If the telephone was not enough, the sound of the lift moving up (without a passenger) plays another aural reminder of Leone's cleverness behind the camera.

The structure. Leone's screenplay of switching from the present to the past and vice versa increases the entertainment value. Coppola's work was linear and less demanding of the viewer. In many ways Leone's work comes very close to the Coppola's third Godfather film--his least appreciated Godfather film, which mixes pathos, irony and closure to intrigues. Leone's film is many ways quite philosophical as was Coppola's Godfather III--far removed from the brutal and power-hungry Godfather I and II. Leone was able to add a dash of comedy--scenes with antics of the Artful Dodger in Carol Reed's Oliver! are copied in the sequences of the early years. Leone's comedy can span from a simple act of hungry boy eating a cream pastry that he had bought to impress his love interest to a young girl taunting her boy lover that "his mother is calling" when his male friend whistles. Coppola's cinema rarely dealt with comedy, unless it was a precursor to tragedy. Several sequences where Leone switches time--the eyes of the protagonist changing from the old to the young man, the appearance of the protagonist in the railway station, and the Frisbee hitting the protagonist as he walks the lonely cold street--makes the film more exciting and colorful. The long film is suddenly less boring as it entertains you while unfolding the saga. The switching of the female child with the male, the corruption among the law enforcers, and the obvious dwarfing of the female characters against the male parts for Leone appears more pronounced than in Coppola, because the intent is to underline the weakness of male folly at the height of their power.

The film is Leone's essay on American's interest in getting rich and powerful at the cost of simple values of honor and friendship. At the end the director emphasizes the importance of honor and friendship even among gangsters and even women who often ultimately seek the rich guy to live with rather than the true lover.

The effect of De Niro's final laugh at the camera can be interpreted in several ways. Who is he laughing at? The camera? The audience? The irony of his life? Is the chase for money worth it? It reminds me of Richard Burton's character, a vicious bank robber, who in the final shot of the remarkable British film Villain (1971) turns around at the camera and shouts "Who do you think you are looking at?"

Leone could not have made Godfather I or II, but he could have dealt with Godfather III. And Coppola could never have made Once upon a time in America. Leone's decision to change the name of the film from the novel's name The Hoods gives an indication of where the director is leading the audience.

The more you see the film you realize the film is a robust one that will stand the test of time because Leone did not want to merely present an interesting saga on screen but entertain intelligently.

Any Leone fan would know the importance the director gives to music, structure of the story, the importance of money and how it corrupts many values. All these elements are underlined in this gangster film. In Coppola's work, the story afforded more importance to social details, character details and fabulous camera-work. Both works are monumental--but I preferred Leone's work, truncated to less than 4 hours than his original cut of 6 hours.

The music. Leone's favorite Ennio Morricone provided one of the finest film music for this film and he won awards for this film as he had won praise for Leone's The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly and a host of other spaghetti westerns by Leone. But the real contributor of music was a Romanian flute player called Georghe Zamfir who plays the brilliant, haunting Pan's song just as Zamfir played the same tune equally effectively in Australian Peter Weir's Picnic at Hanging Rock made 9 years before Leone's film. Weir and Leone both know their music and both need to be complimented for picking up this obscure Romanian to enhance their films. Leone's cinema does not limit to brilliance of music--he uses sound to give effects that surpass the camera eye. The ringing telephone--a telephone ring that persists before the number dial moves on the instrument--provided a stamp of Leone that no viewer will easily forget--and no director had accomplished so effectively. Of course, the telephone call was so central to the film's plot. If the telephone was not enough, the sound of the lift moving up (without a passenger) plays another aural reminder of Leone's cleverness behind the camera.

The structure. Leone's screenplay of switching from the present to the past and vice versa increases the entertainment value. Coppola's work was linear and less demanding of the viewer. In many ways Leone's work comes very close to the Coppola's third Godfather film--his least appreciated Godfather film, which mixes pathos, irony and closure to intrigues. Leone's film is many ways quite philosophical as was Coppola's Godfather III--far removed from the brutal and power-hungry Godfather I and II. Leone was able to add a dash of comedy--scenes with antics of the Artful Dodger in Carol Reed's Oliver! are copied in the sequences of the early years. Leone's comedy can span from a simple act of hungry boy eating a cream pastry that he had bought to impress his love interest to a young girl taunting her boy lover that "his mother is calling" when his male friend whistles. Coppola's cinema rarely dealt with comedy, unless it was a precursor to tragedy. Several sequences where Leone switches time--the eyes of the protagonist changing from the old to the young man, the appearance of the protagonist in the railway station, and the Frisbee hitting the protagonist as he walks the lonely cold street--makes the film more exciting and colorful. The long film is suddenly less boring as it entertains you while unfolding the saga. The switching of the female child with the male, the corruption among the law enforcers, and the obvious dwarfing of the female characters against the male parts for Leone appears more pronounced than in Coppola, because the intent is to underline the weakness of male folly at the height of their power.

The film is Leone's essay on American's interest in getting rich and powerful at the cost of simple values of honor and friendship. At the end the director emphasizes the importance of honor and friendship even among gangsters and even women who often ultimately seek the rich guy to live with rather than the true lover.

The effect of De Niro's final laugh at the camera can be interpreted in several ways. Who is he laughing at? The camera? The audience? The irony of his life? Is the chase for money worth it? It reminds me of Richard Burton's character, a vicious bank robber, who in the final shot of the remarkable British film Villain (1971) turns around at the camera and shouts "Who do you think you are looking at?"

Leone could not have made Godfather I or II, but he could have dealt with Godfather III. And Coppola could never have made Once upon a time in America. Leone's decision to change the name of the film from the novel's name The Hoods gives an indication of where the director is leading the audience.

The more you see the film you realize the film is a robust one that will stand the test of time because Leone did not want to merely present an interesting saga on screen but entertain intelligently.

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

13. German director Wim Wender's US film "The Million Dollar Hotel" (2000): Stamp of a mature director

Here's an American film made with a European touch that provides social, psychological and political commentary. The story was conceived and the music provided by Bono (of U-2 fame). U-2, incidentally, provided the music for many of Wim Wender's recent films.

I watched this Wim Wenders film, 25 years after I last saw a film by this German director. I have only seen two others Kings of the Road and The Wrong Movement both made in the mid-Seventies. Wim Wenders impressed me then, he impresses me now. He is a social commentator who loves to deal with alienated individuals. He is a German who loves Americana, its varied hues of lifestyles and contrasting views of life.

The opening helicopter shot caressing the sleek LA skyscrapers well clad in glass and steel ends up with the skeleton of the Million Dollar Hotel neon sign. In the background an airplane is taking off. Those who recall Kings of the Road will remember a similar scene in a lonely landscape.

The film is not a mystery film. It is more a reflective, surrealist, social commentary. The first shot of the Mel Gibson FBI character is from his shoes only gradually revealing the man in the shoes. The man in the shoes is a modern Don Quixote, patched up by medical technology. No one in the film is real--each character is unreal with element of realism. Each statement of the script is loaded with social comment. Example "you have to vote in a democracy with a Y or a N, a Y for why and N for why not.." Everyone is manipulating everyone: the media moghul the media, the FBI the suspects, the denizens of hotel each other, the hotel owner his guests, the music business the musicians..If you are attentive the film is hilarious in its wacky social commentary. It reminded me of the fine Danny Kaye (his last regular movie) film The Mad Woman Of Chaillot directed by Bryan Forbes and based on Jean Giradoux' play, where the characters are equally farcical, while the social commentary is sharp as a knife.

Wim Wenders in America is different from Wenders in Europe. He uses American clichés but his cinema remains European. That Gibson contributed his role without pay underlines Gibson's respect for Wenders. Wenders belongs to the era of German cinema (the Seventies) that spewed many talented filmmakers: Syberberg, Fassbinder, von Trotta, Schlondorff, Herzog and Hauff. That this film's true content and value are lost on many Americans is a social comment that must have amused Wenders. Wenders has not withered, he is as effective as he was in his prime, combining strong scripts with fascinating images and marrying both with good music.

See the movie and let the allegories sink in--a hotel that hosts mentally challenged people, too poor to afford medical insurance. If you can figure out the allegories, the movie is a treasure trove.

I watched this Wim Wenders film, 25 years after I last saw a film by this German director. I have only seen two others Kings of the Road and The Wrong Movement both made in the mid-Seventies. Wim Wenders impressed me then, he impresses me now. He is a social commentator who loves to deal with alienated individuals. He is a German who loves Americana, its varied hues of lifestyles and contrasting views of life.

The opening helicopter shot caressing the sleek LA skyscrapers well clad in glass and steel ends up with the skeleton of the Million Dollar Hotel neon sign. In the background an airplane is taking off. Those who recall Kings of the Road will remember a similar scene in a lonely landscape.

The film is not a mystery film. It is more a reflective, surrealist, social commentary. The first shot of the Mel Gibson FBI character is from his shoes only gradually revealing the man in the shoes. The man in the shoes is a modern Don Quixote, patched up by medical technology. No one in the film is real--each character is unreal with element of realism. Each statement of the script is loaded with social comment. Example "you have to vote in a democracy with a Y or a N, a Y for why and N for why not.." Everyone is manipulating everyone: the media moghul the media, the FBI the suspects, the denizens of hotel each other, the hotel owner his guests, the music business the musicians..If you are attentive the film is hilarious in its wacky social commentary. It reminded me of the fine Danny Kaye (his last regular movie) film The Mad Woman Of Chaillot directed by Bryan Forbes and based on Jean Giradoux' play, where the characters are equally farcical, while the social commentary is sharp as a knife.

Wim Wenders in America is different from Wenders in Europe. He uses American clichés but his cinema remains European. That Gibson contributed his role without pay underlines Gibson's respect for Wenders. Wenders belongs to the era of German cinema (the Seventies) that spewed many talented filmmakers: Syberberg, Fassbinder, von Trotta, Schlondorff, Herzog and Hauff. That this film's true content and value are lost on many Americans is a social comment that must have amused Wenders. Wenders has not withered, he is as effective as he was in his prime, combining strong scripts with fascinating images and marrying both with good music.

See the movie and let the allegories sink in--a hotel that hosts mentally challenged people, too poor to afford medical insurance. If you can figure out the allegories, the movie is a treasure trove.

Sunday, September 17, 2006

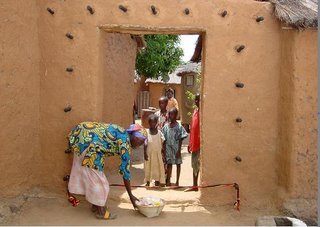

12. Senegalese director Ousmane Sembene's "Moolaade" (2004): Africa ought to be proud of this film!

Ousmane Sembene is a colossus among African filmmakers. He is what Kurosawa and Ray are to Asia. At 82, this man is making films on women's problems, on colonialism, on human rights without losing sight of African culture.

Moolaade deals with rebellion by African women against female circumcision, a tradition upheld by elders, Muslim and animist, in a swathe of countries across Saharan and sub-Saharan Africa. Interestingly, the film is an uprising within the social traditions that allow the husband full powers over his wives and acceptance of other social codes to whip his wife in public into submission. How many women (and feminist) directors who preach about female emancipation would have dared to make a film on this subject in Africa? The subject could cause riots in countries such as Egypt. Sembene is more feminist than women and I admire this veteran for this and other films he has made. He graphically shows how women are deprived of sexual pleasures through this practice and how thousands die during the crude operation.

Moolaade deals with other aspects of Africa as well. It comments on the adherence to traditional values that are good--six women get protection through a code word and piece of cloth tied in front of the entrance to the house. It comments on materialism (including a bread vendor with a good heart for the oppressed who is called a "mercenary" by the women who claim to know the meaning of the word) that pervades pristine African villages (the return of a native from Europe and the increasing dependence on radios for entertainment and information).

Sembene's cinema is not stylish--its style stems from its simplicity and its humane values. Sembene's films allow non-Africans to get inside the world of the real Africa far removed from the world of the Mandelas, constant hunger and the epidemic of AIDS that the media underlines as Africa today. Sembene's film is not history, it is Africa today. The performances are as close to reality as you could get.

At the end of the film shown at the 2005 Dubai Film Festival, I could not but marvel at a man concerned not at making great cinema for arts' sake but using it creatively to improve the human condition of a slice of humanity the world (and the media) prefers to ignore. How many of us worry about the conditions of life in Africa, let alone the social problems of women in Africa? Here is a director nudging us to think on those lines. Through this film, a subject that most Muslims prefer not to discuss is brought to the screen.

Saturday, September 16, 2006

11. Valerie Guignabodet's French film "Mariages!" (2004): Weaving entertainment from strands of reality

The film is an essay on marriages. Robert Altman tried to do the same in A Wedding and ended up with a delectably visual and aural feast that missed your heart by a mile. Altman tried to approach the subject as a black comedy, while this French film reaches out truthfully to lay bare all the charades between man and woman as seen through the lives of different married couples over a couple of days. Altman is a man; Valerie Guignabodet is a woman--viva la difference! Guignabodet unlike Altman is not worried about the ceremony; Guignabodet is more interested in dissecting the cadaver as in an autopsy. In the end, her final shot of the bride's mother walking away taking the middle path (literally and figuratively) away from it all is a masterstroke. The end, in some ways, is better than the rest of the film because it makes a mute statement. (Remember the comparable end of Mazursky's An Unmarried Woman?)

The rest of the film belongs to the actors--the most underrated actress in the world Miou-Miou (see her in Claude Miller's Dites-lui que je l'aime or that brilliant Netoyages a sec) and the arresting Mathilde Seigner. True they have great lines but they make the characters leap out the screen, however small (a teeny weeny Air France seat TV screen in my case).

The film is unusual--it has sex but never visually shown. The film captures the effect on other characters in the movie. The social jibes at the British (thru a fictional Kenneth Branagh who never appears) and the East Europeans (a Pole who is seen as Russian) could easily have been an Altman effect, but director Guignabodet is able hit you below the belt as she makes jabs after jabs at various social institutions, e.g., replacing the wedding march music with pathos, the best man who forgets the rings, traditional marriages compared to modern ones, role of gays vs. heterosexuals at marriages. A true blue-blooded French film, if ever there was one. The French do know the art of leaving the viewer to reflect on insitutions other nationalities take for granted. This is a fine example where the debate begins in the mind of the viewer as the film spool runs out.

P.S. Not many films titles have exclamation marks at the end. Therein hangs a tale!

The rest of the film belongs to the actors--the most underrated actress in the world Miou-Miou (see her in Claude Miller's Dites-lui que je l'aime or that brilliant Netoyages a sec) and the arresting Mathilde Seigner. True they have great lines but they make the characters leap out the screen, however small (a teeny weeny Air France seat TV screen in my case).

The film is unusual--it has sex but never visually shown. The film captures the effect on other characters in the movie. The social jibes at the British (thru a fictional Kenneth Branagh who never appears) and the East Europeans (a Pole who is seen as Russian) could easily have been an Altman effect, but director Guignabodet is able hit you below the belt as she makes jabs after jabs at various social institutions, e.g., replacing the wedding march music with pathos, the best man who forgets the rings, traditional marriages compared to modern ones, role of gays vs. heterosexuals at marriages. A true blue-blooded French film, if ever there was one. The French do know the art of leaving the viewer to reflect on insitutions other nationalities take for granted. This is a fine example where the debate begins in the mind of the viewer as the film spool runs out.

P.S. Not many films titles have exclamation marks at the end. Therein hangs a tale!

Thursday, September 14, 2006

10. Aki Kaurismaki's Finnish film "Mies vailla menneisyytta" (2002) (A Man Without a Past)--Reducing the world into a man, a woman, a dog and trains

This movie is deceptive--a casual viewing could discard it as another "feel good" film from Europe.

It permeates Christian values without sermons, priests, or any religious hard sell (a small poster of Christ in a booth of the Salvation Army is an exception). Philosophically, it presents Tabula Rasa or a clean slate to begin life anew. The film tends to be absurdist (not even a moan emanates from brutalized victims of violence, broken noses are twisted back painlessly, victims of violence emerge from shadows to mete out justice). The film recalls shades of the brilliance of Tomas Alea's early Cuban films and the humanity of Zoltan Fabri's Hungarian cinema.

The film presents entertainment of a kind that would be alien to Hollywood--a cinematic essay on human values that seem to be a rare commodity the world over. There is no sex; there is no need for it. The poor who live in garbage bins and in empty containers, are rich with pockets full of kindness, helping each other without any expectation of a reward. The rich and powerful (the ex-wife and her lover, the policemen, the hospital staff, the official who rents out illegal living space) seem bereft of true feelings or any human kindness. The poorer sections of society (the electrician, the restaurant staff, the family who nurses the main character, the Salvation Army staff) do good to others, care about others and expect nothing in return.

The film is an affirmation of Christian values without preaching religion. The main female character in love with the man, is ready to sacrifice her love because she genuinely respects marriage vows and even brings a "train" schedule to send off her lover to his wife. The art of giving is sanctified. A man who employed workers believes in paying his workers, even if it meant robbing a bank to do so. A lawyer argues a case well because he likes the Salvation Army. Symbolically, even half a potato among six or eight harvested is given away to some stranger wanting to eat it and avoid scurvy! Again, symbolically there is rain on a clear day to help grow the few potatoes...

The film provides humour of a quaint, Finnish variety. A timid dog that eats leftover peas is called Hannibal--a male name one can associate with a king or even the cannibalistic Hannibal Lecter--even though the dog is female. There are swipes taken against the government and its associated machinery (antiquated laws, North Korean buying Finnish banks, retirement benefits, strikes and strikers, bank staff, corrupt banking practices).

Trains play a crucial role in Kaurismaki's screenplay. It begins and ends the film. It also punctuates the film, when the past is revealed, briefly.

There are possible flaws in the film--the blue tint when the children spot the injured man. The unexplained Japanese dinner with Sake and Japanese music on the train. The significance of the cigar in the script is elusive. The choice of songs, however good, seem to be haphazard.

The script is otherwise brilliant. In glorifying the detritus of society, Kaurismaki seems to affirm there is indeed a link between the tree and falling dead leaf (with reference to a comment by a character in the movie). The train moves on. Forward, not backwards!

Minimizing the world into a man, a woman, a dog and trains, Kaurismaki serves a feast of observations for a sensitive mind--a tale told with a positive approach to move on and seize the day. It is a political film, an avant garde film, a comedy and a religious film, all lovingly bundled together by a marvelous cast.

Finland should thank Kaurismaki--he is her best ambassador. He makes the viewer love the Finns, warts and all!

It permeates Christian values without sermons, priests, or any religious hard sell (a small poster of Christ in a booth of the Salvation Army is an exception). Philosophically, it presents Tabula Rasa or a clean slate to begin life anew. The film tends to be absurdist (not even a moan emanates from brutalized victims of violence, broken noses are twisted back painlessly, victims of violence emerge from shadows to mete out justice). The film recalls shades of the brilliance of Tomas Alea's early Cuban films and the humanity of Zoltan Fabri's Hungarian cinema.

The film presents entertainment of a kind that would be alien to Hollywood--a cinematic essay on human values that seem to be a rare commodity the world over. There is no sex; there is no need for it. The poor who live in garbage bins and in empty containers, are rich with pockets full of kindness, helping each other without any expectation of a reward. The rich and powerful (the ex-wife and her lover, the policemen, the hospital staff, the official who rents out illegal living space) seem bereft of true feelings or any human kindness. The poorer sections of society (the electrician, the restaurant staff, the family who nurses the main character, the Salvation Army staff) do good to others, care about others and expect nothing in return.