Why did I like the film? I applaud any director making his or her initial film who chooses to film a complex subject like Shakespeare's least known tragedy, probably the mother of all his well-known tragic plays King Lear, Othello, Macbeth, Hamlet, and Julius Caesar that literature critics have dubbed a "problem play." It is true that each of the later Shakespeare tragedies borrowed strands from Titus Andronicus. Shakespeare staging Titus Andronicus was in a way similar to Julie Taymor's effort to film the play. Shakespeare wanted to establish his name. Some even suggest that Shakespeare did not write it but borrowed the source material. Yet no one can dispute that even in Elizabethan times, the play went down well with audiences. And Shakespeare went on to write and stage more plays. But for years the play was a problem to put on stage and it is well-known that few directors chose to stage or film it, due to its gory and dark contents.

I applaud Julie Taymor's decision to pick up the play to film. Titus, the play, is relevant today even more than it was in Elizabethan days. Titus is replayed almost each day in the Middle East, in Darfur, and till recently in former Yugoslavia, in Rwanda, and in Ireland. I am delighted that Taymor chose to rework the play mixing the past Roman glory with those of Mussolini's Italy, which underlines the relevance of the play today—irrespective of whether the conquering heroes ride horses or Rolls Royces.

I congratulate Taymor's decision to create a modern "chorus" distilled in the personality of a young boy, who plays like an adult but is "shaken and stirred" by events outside, who seems to realize as the play unfolds the importance of forgiveness, tolerance and love for all. For the Greeks and even for Shakespeare, the chorus had to be old and blind (as in Macbeth) but for Taymor it's the young who have eyes to see the dawn after the dark night.

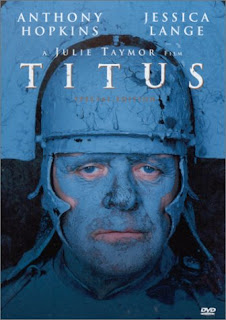

There are more facets to the film that make the film extraordinary. Jessica Lange's Tamora presents a range of emotions—crying for pity, yelling for revenge, smiling to seduce and aroused by a kiss of her mortal foe Titus. The short kiss of the aging Titus and Tamora is a highlight of the film, the kiss between conqueror and former slave, a kiss between a queen and a demented subject—all highlighted by the facial expression of Ms Lange choreographed by Taymor. This brief shot cries for our attention, as throughout the film (and play) Titus seems to be celibate. (There is no mention of Titus's wife or lover). I thought Taymor brought out the best in Ms Lange, even exceeding her range of emotion in Frances. While Anthony Hopkins might not have enjoyed making this film, Taymor brought out his finest performance to date here in this film. It was almost like watching a mellow Richard Burton rendering the lines of the Bard. Taymor and cinematographer Luciano Tavoli, who is often arresting, are able to obtain a shot of Titus crying on the stony paths, with his face and eyes inches from the stones, signifying the lowest of the low the character has been hewn down to the terra firma.

A third commanding performance was that of Alan Cumming as Saturinus, second only to his mesmerizing role in Eyes Wide Shut as a gay front office clerk. If you reflect on the film, the casting was superb.

The only flaw in the "absurdist" treatment was the introduction of the Royal Bengal tiger—which could have been replaced by a leopard or a lioness. This I thought was taking the theater of the "absurd" too far. Perhaps Taymor wanted to glamorize Tamara to be more attractive as the tiger than any other great cat. That was one decision I thought did not work well in the movie.

The film's strengths are not restricted to the screenplay, the direction and acting. The film grips you with the music and choreographed title sequence and the overall production design. You want more. You get more, if the viewer is able to think while watching the film and think laterally. This is not Gladiator or Spartacus. It challenges the senses, beyond the gore and sex. Why do people behave as they do? Is the bias of many of us limited to race and color? These are questions that Terence Mallick asked in The Thin Red Line. To appreciate Taymor's Titus multiple viewings will help, preferably with a thinking cap. I rate this film as third best Shakespeare film ever made—the first two being the Russian black and white films Korol Lir (King Lear) and Gamlet (Hamlet) directed by Grigory Kozintsev, some 40 years ago.

Finally, like Orson Welles and Terrence Mallick, Julie Taymor appears to be little appreciated within the US but more lauded elsewhere. But that should not dampen the brilliance of this talented lady and her spouse the music composer Elliot Goldenthal.

P.S. Kozintsev's King Lear (Korol Lir) is reviewed elsewhere on this blog. Titus is one of the author's top 100 films.

No comments :

Post a Comment