Winter Light is simply stunning cinema. Ingmar Bergman realized this was the film (with the arguable exception of Fanny and Alexander) that satisfied him most among his entire body of work. And this was not a casual remark made by a director to promote his film soon after he made it, it was instead a written statement he made 25 years after the film was made. Viewing the black-and-white film a few days after Bergman died, I could not but agree with his view. It is a great film from a great director. It is a film that average audiences might never appreciate. Even Bergman’s wife (at that time) found it dreary. It would make sense to viewers familiar with theology (Bergman was the rebellious son of a Lutheran priest) and much of the gravity of the film will be lost to those unfamiliar with the issues presented in the film. Yet it is a film that would provide adequate material to atheists and believers alike in equal measure. It’s a thinking-person’s film.

If the rules of aesthetics of Aristotle’s Poetics were to be applied to cinema, Winter Light would be perfect cinema. It begins and ends in a church (though the churches are different ones close to each other with the same organist and the same sexton). It begins and ends within a 24-hour period. Much of the action can be correlated (mimesis) to Christ’s Last Supper leading up to his death on the cross. Catharsis abounds both for a believer and non-believer. The main character undergoes anagnorisis or self realization through the accusatory statements of his lover. There is arguable peripeteia (reversal of circumstances) as non-believing lover prays by kneeling with folded hands in the penultimate shot soon after the organist who also attends Free Mason rituals exhorts her to leave the Church and her love, the widower Priest.

Most critics bypass this particular work of Bergman for good reasons. It is totally devoid of music, if you discount the church bells and the organ played in the church. It does not have the hypnotic visual allure of The Seventh Seal or of Sawdust and Tinsel. It has unusually long sequences of actors speaking into the camera. Its actors are all ugly, anti-heroic, and stunted (even the beautiful blonde Ingrid Thulin appears here in major role as a homely brunette destined to remain a spinster). It’s a film about suicide, about physical suffering, and about cold Scandinavian winters. Like David Lean’s Ryan’s Daughter and John Huston’s fascinating adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ The Night of the Iguana, the film is populated with anti-heroes, cripples and losers. Finally, the film is overtly theological. All these are facets of cinema that rarely makes viewers sit up these days.

Why then is this movie stunning?

It has an absolutely flawless structure for its screenplay. It begins and ends with a church service. The number of worshippers seems to diminish towards the end of the movie but the few believers are stronger in faith. The scene after opening service and the scene before the final service are both in the vestry. The middle sections take the action out of the church. This structure would have pleased the ancient Greek playwrights and Shakespeare alike.

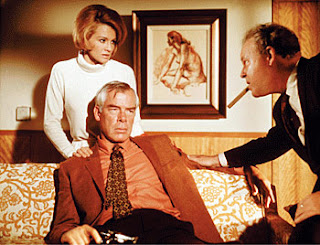

Every scene, every sequence is carefully created. You remove one and the whole film collapses. The use of light and shadows is awesome in each and every scene (see the scene above). Each scene provides fodder for reflection. Take the scene where the priest and his lover stop at a level crossing. The line spoken by the priest is that he entered priesthood because his father told him to become one. An innocent statement, if you do not know Bergman was the son of a priest and that Through a Glass Darkly the previous work in the trilogy ended with a crucial conversation on God between father and son. Through a Glass Darkly ended with the son (Minus) asking his father (David): “Give me a proof of God.” His father answered: “I can only give you an indication of my own hope. It’s knowing that love exists for real in the human world. . . . The highest and lowest, the most ridiculous and the most sublime. All kinds. . . . I don’t know whether love is proof of God’s existence, or if love is God. . . . Suddenly the emptiness turns into abundance, and hopelessness into life. It’s like a reprieve, Minus, from a sentence of death.” Visually, too, the stop at the railway crossing offers food for thought. Some critics aver that the railway wagons passing by the stopped car have remarkable similarity to coffins.

The spoken words throughout are intense and often interlink this film with Bergman’s previous film in the trilogy Through a Glass Darkly, where the leading lady having a nervous breakdown has visions of God as a spider. In Winter Light, the connection is made with the words of the priest: “Every time I confronted God with the realities I witnessed - he turned into something ugly and revolting. A spider god, a monster. So I fled from the light, clutching my image to myself in the dark.”

Similarly, the link to the next film in the trilogy The Silence, is made by the words: “When Jesus was nailed to the cross -and hung there in torment - he cried out -"God, my God!" "Why hast thou forsaken me?" He cried out as loud as he could. He thought that his heavenly father had abandoned him. He believed everything he'd ever preached was a lie. The moments before he died, Christ was seized by doubt. Surely that must have been his greatest hardship? God's silence.”

Doubt about the existence of God is the underlying theme of the Bergman trilogy. It is not a coincidence that the main character is called Rev. Tomas after Thomas the doubting Apostle who refused to believe in Jesus' resurrection until he put his finger in his Jesus’ nail wounds.

The film’s end offers both a comforting interpretation to non-believers and another one to believers. When Bergman wrote the script, he was rebelling against his father who was a devout believer. The end of the film was crafted by Bergman after he saw his old father insisting on all the prayers said in a church when the regular priest was too ill to say them.

Existential non-believers will argue that in the final scene of Winter Light, the priest who knew he could not honestly help a man about to commit suicide, lamely continues his vocation without conviction. Believers will interpret the same scene to mean that the wretched priest realizes that silence from God does not mean that God does not exist but that he has to toil and suffer with added conviction and begin once again with a single worshipper to populate the near empty church. We can surmise that the priest will marry again because his new wife will now not be struck by his “indifference to (his) Jesus Christ” and that the crippled sexton finds a new supporter for his viewpoint that physical pain is easier to bear than loneliness.

For those viewers familiar with an Indian/Malayalam national-award winning film Nirmalayam, (directed and written by M T Vasudevan Nair in 1973), the end of the two films are worthy of comparison. The major characters in both films suffer psychological stress. Both characters are priests and religious (though practising different religions). Yet the final action of both are interestingly different. Both are interesting screenplays and worthy films. Both movies give ample room to the viewer for thought.

Either way, the two films offer considerable options of interpretation for a sensitive, intelligent viewer.

P.S. Through a Glass Darkly was reviewed earlier on this blog. Winter Light is one of the 10 movies that director Andrei Tarkovsky listed before his death as the best works of world cinema.