|

| Frozen lake |

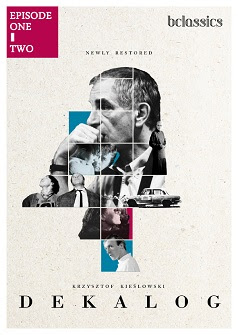

The ten-part Dekalog is definitely one of the 10 best works of cinema ever made for this critic. Each segment of the ten-part film Dekalog is linked to the 10 Commandments given by God to Moses as believed by Christians, Jews and Muslims.

Now many who are not familiar with subtle changes introduced into various versions of the Bible over time would assume the

Ten Commandments are written in stone and will have to be the same in all published

versions. This, unfortunately, is not the case. One reason for the differences pertains

to sources of the Commandments (The Septuagint,

Philo’s Septuagint, The Samaritan Pentateuch, the Jewish Talmud, and The Holy Koran’s sura Al An’am and al Isra) and the second, the various interpreters (St Augustine, Martin Luther and John

Calvin). (Ref: Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ten_Commandments )

When Krzysztof Kieślowski made Dekalog in collaboration with co-scriptwriter

Krzysztof Piesiewicz one can guess each of the Ten Commandments, each episode

refers to in broad terms. But a detailed

evaluation brings into the limelight the conflict of the tale of some episodes

of Dekalog with various differences in the numbering of

the Ten Commandments and the subtle differences of how each Commandment reads, depending on the particular faith of the viewer.

Now Dekalog, One refers to the First Commandment I am the Lord thy God, thou

shalt have no other gods before me. The

story of Dekalog, One can be

deconstructed to accommodate two conflicting

views about God derived from two adults in the life of a 12 year old precocious boy called Pawel. The father, Krzysztof, is a university professor

who believes in reason and scientific methods. Pawel’s mother is apparently

abroad. Pawel has an aunt Irene (Krzysztof’s

sister) who deeply believes in God unlike her brother.

Young Pawel is close to his father

and shows off the computer skills he has learnt from his father to his aunt

Irene. He can lock the door of his apartment using remote control with the help

of the computer. He can even open water faucets by a similar method. However,

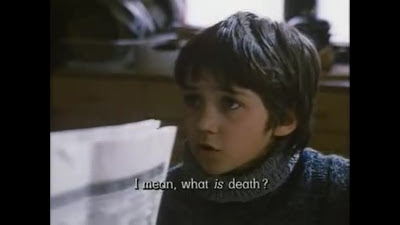

the clever Pawel is also a sensitive boy who is shaken by the sight of a

familiar stray dog that has died near his apartment.

When Pawel asks his father “Why do people die?” his father answers: “It depends—heart failure, cancer,

accidents, old age..”  |

| The million dollar question from a 12-year old |

Pawel persists: “I mean what is death?”

His father Krzysztof explains, “The heart stops pumping blood. It does not reach the brain. Movement ceases. Everything stops. It is the end.”

Pawel continues “So what is left?”

The father answers his son: “What a person has achieved; the memory of

that person. The memory is important. “

Now the film’s character Krzysztof

could easily be associated with (or an extension of) its director Krzysztof Kieslowski,

who had publicly stated that he was an atheist. The third Krzysztof of the film

is the co-scriptwriter Krzysztof Piesiewicz, who is publicly a Roman Catholic. This critic is convinced that Piesiewicz is possibly one of the finest scriptwriters in the history of cinema even though he is primarily a politician and a lawyer.

|

| Pawel's aunt Irene is the optimistic theist |

In this amazing film, despite all

the knowledge and scientific reasoning and calculations and a physical personal

check of the ice that covers the frozen lake, the ice breaks. There does seem to be a parameter beyond

science and reason and physical reassurance that the calculations are

correct. Krzysztof, the father,

calculated if his son’s weight could crack the ice and found the ice would

hold. For the university professor, computers, mathematics and reason, is more trustworthy

than God. In 1989 Poland, computers and

computation was the new God. As a good father, to reassure his own calculations,

he himself goes on the ice to see if it could hold his adult weight. He is reassured as the ice holds. Yet, tragedy

follows.

There is sufficient evidence on

the IMDB portal’s page on Piesiewicz that Dekalog,

One, Two, Seven and Eight are

four episodes that were originally written by Piesiewicz. These are four of the

most intriguing episodes of the 10. Conversely the other six were originally

written by Kieslowski, with additional inputs from Piesiewicz.

If we accept the Piesiewicz

contribution to Dekalog, One being

more than that of Kieslowski, plot wise, the end of this episode falls into

place. The devastated, emotionally broken, rational father goes to the church

under construction to make peace with God. The makeshift wooden altar breaks. The falling lighted candles drip white wax on

the iconic figure of the Black Madonna of Czestochowa, giving the impression that

the Madonna was crying. (Dekalog, One opens

with a shot of aunt Irene crying as she watches television breaking news on the

streets.) As the emotionally broken father leaves the church, as a good Roman

Catholic he dips his hand in the receptacle containing holy water. The water is

partly frozen. A former rational professor

pulls out a piece of ice resembling a Host wafer from the receptacle and contritely presses

it on his forehead by himself. What a wonderful symbol of accepting God above all

his rational calculations. Was Kieslowski really an atheist as he claimed to

be?

P.S. Dekalog is included in the author's top 10 films. Three other episodes: Dekalog, Two; Dekalog, Five; and Dekalog, Seven have been reviewed earlier on this blog. The reviews of

This critic was fortunate to have met and talked with director Kieslowski in Bengaluru, India, in January 1980 when his collaboration Piesiewicz had yet to begin. Dekalog, Three Colours: Blue, White and Red, and The Double Life of Veronique were yet to be made. This critic ardently hopes to meet with Piesiewicz to ask him about those films and Kieslowski, now that Kieslowski is no longer with us.

This critic was fortunate to have met and talked with director Kieslowski in Bengaluru, India, in January 1980 when his collaboration Piesiewicz had yet to begin. Dekalog, Three Colours: Blue, White and Red, and The Double Life of Veronique were yet to be made. This critic ardently hopes to meet with Piesiewicz to ask him about those films and Kieslowski, now that Kieslowski is no longer with us.