Krzysztof Zanussi (84) has won the Golden Lion at the Venice film festival for his film A Year of the Quiet Sun (1984), the Jury prize at the Cannes film festival for The Constant Factor (1980)., the Golden Leopard at Locarno film festival for Illumination (1973), among 69 international awards. The latest is his Lifetime Achievement Award bestowed by the International Film Festival of Kerala, India. He spoke to the author of this blog, Jugu Abraham.

|

| Mr Zanussi addressing the media at IFFK on 14 Dec 2023 at Trivandrum, Kerala |

|

| Mr Zanussi listening to his interviewer, Mr Abraham |

Zanussi: Even though Kieslowski wrote all the screenplays with his personal friends as co-scriptwriters, he was responsible for the stories. He was the leading writer. We were very close friends.

Abraham: In your case, most of the scripts are your own.

Zanussi: I hope it is. It's up to you to judge.

Zanussi: Wege in der Nacht

Abraham: Yes, The way you structured it was fascinating for me, because your script split it into three parts. One on the love affair between a good Nazi and a Polish aristocratic lady; another on the past history of the Nazi officer, and the final segment of the Nazi’s daughter and her strange comments on the affair concluding the film, a segment that would force viewers to reassess the film altogether. Several decades later, Russian director Konchalovsky has done the same with his film Paradise. Not many other directors have employed this radical structure.

Zanussi: Glad to hear that. And as this film is forgotten, I am very happy that you are one of my viewers. I was inspired by some situation in my own family. So it is a very personal film. Of course, everything is remodeled. But the whole idea of a good German, a good enemy, is something very intriguing to me. And at the time, when I was writing this film, it was in the 70s . I was very much afraid that being the subject, a citizen of a country in the Soviet bloc, I will be forced to take part in the war that they were announcing all the time. And we knew in Poland, the Polish army was supposed to go against Denmark. And that I could be some day, probably be an interpreter in the army, I will be soon be facing my acquaintances, my friends in Denmark, telling them get out of their house, because some Soviet officer would be staying there This was a frightening prospect. So I did identify with the German as much as with the Polish character. I thought each of them is in a tragic position. Culture is not enough to make peace between two people who are on opposite sides of a war.Abraham: Probably you're aware of it that subconsciously you had created two well-educated personalities as the two lovers, and that they have read a lot more than the others.

Abraham: And that made

the difference to the entire story. And this resurfaces in the

rest of your work as well. It's the people who are well read, who are often good

people listening to their conscience and making the right decisions..

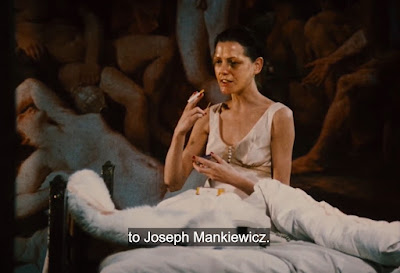

Abraham:. And also, you are able to do something special with Maja Komorowska, one of your favorite actresses who has been with you.in so many later films of yours. In this particular film, she stole my heart. I mean, even though later on, she has done so many works (A Year of the Quiet Sun; In Full Gallop), which were equally good. But this early work was remarkable.

Zanussi: I will definitely will tell her, Yes, because we're still friends, and still in touch. She's still active, even though she's even older than myself. And she is still active on stage, occasionally she does some some roles in films.

Abraham: We see her later on in your film A Year of the Quiet Sun, portraying a different character. There again, her character is almost similar to her character in Ways in the Night underscoring that people who have a good conscience, do the right thing. And I think that comes as a recurring theme that goes through all your films, that taking the right moral action is very important, in spite of everything else.

Zanussi: While trying to be right, there are some tragic situations where there is no good way out as in my film Camouflage. When if you don't quit, you're guilty, even if you have good intentions. That's a tragic situation that we know from Greek drama. Right. But that's what we try to avoid. In fact, whenever I'm confronted with India, I wonder how you manage to avoid tragic aspects because you have Sanskrit drama and I try to read some of them. But there is no tragedy but there is drama and conflicts but there is always a way out. And there is always an original order original harmony yes, that you can restore at the end. Right? I think there's a very big cultural difference between Europe and India.

Abraham: Contemporary playwrights have taken up the aspect of tragedy in contrast to, as you point out, the original ancient ones. You might have heard of the late Girish Karnad as a playwright and filmmaker. He wrote Tughlaq, which is a very interesting tragic play, I always wondered why nobody has picked up that play to make a film. And it's a historical character, which is a tragedy and a beautiful one. I've happened to have acted in that play when I was in college.

So, apart from that, I

noticed that you have often reverted to casting some of the actors whom you

worked with earlier on. An example is Scott Wilson.

Zanussi: Oh, yes. How do you go back as a human being? As a married man I have only married once! Yes. So I have a natural tendency to be faithful and faithful to my friends, right. So when I have a good experience with an actor, I always invite these actors to my future works, like Leslie Caron, who worked three times with me, and really many others like Maja Komorowska and Zbigniew Zapasiewiecz.. He is such a good example when we talk about well-educated and passionate people. Right. Sometimes education kills your passion. Then the education is not the right education. What it means is that it is the wrong education.

Abraham: Now, let me get back to your physics. Because that's interests me because I too studied physics initially in college. When you started your films career as a director and original screenplay-writer, you dealt with inorganic subjects, and then gradually moved on to organic subjects in films and used them as allegories, For instance, from Structure of Crystals, to mathematics and statistics (Imperative), to physics (Illumination) to even linguistics (Camouflage), and then you go on to inorganic examples in science as in the film Life as a Sexually Transmitted Disease.Zanussi: One thing is stable, that all material world is interconnected.

Abraham: That’s true,

Zanussi: And there was a movement, the first half of the past century was half century of physics. The second is half a century of biology. So I travel with the development of the problems. Now the future of humanity depends very much on biology and genetic engineering, right? Are we going to improve our species or kill it? What’s going to happen?

Abraham: I was surprised that not many people in the US, UK and Latin America are aware of your films except when the early film Ways in the Night came out. The famous US film critic Roger Ebert gave it very high ratings and in his review and stated that you are “one of the best filmmakers in the world..“ Apart from that recognition, not many people are aware of your films in those parts of the world.

Zanussi: I still must be happy that somebody is aware like yourself.

Zanussi: Yes, at the beginning, with a colleague of mine from the film school, who was a writer. He was more advanced than I was. He joined me and we were writing scripts for television, which I made into films later. But once the scripts became more of a story for my first film, we could not agree, I had my vision and he had his. We had a friendly parting of ways. We remained friends for the rest of his life.

Abraham: So you felt that by doing things your own, you probably had a more rounded structure for your screenplays?

Zanussi: No. A different structure. The message was different. My friend was far more negative than I was. So there was no compromise. Either there was hope or no hope.

Abraham: Would you like to say something about your work with Polish music composer Wojciech Kilar, and the music of the composer with whom you have worked on so many of your films? Why did you pick him? And stay with him?

Zanussi: We became friends. The beginning of the friendship was a disaster. And I was guilty of it. I had a crazy idea as young filmmakers have, when you're young, you have ideas that are totally insane. Because I have a good musical ear, no education, I thought I will make a revolution and I will ask music to be written before I make a film, not after. Two composers said it is impossible. And the third one said, I don't say that is reasonable. He wrote the music, I used his music as a playback. Everything was right. Once the film was edited, it looked ridiculous. It was really, really ludicrous. Because when you had a shadow, you had to have something that corresponded to it. So it was like animation. It was a very bad idea. Kilar said that now I will write the real appropriate music for your Structure of Crystals. He wrote it. And since then, I felt I had such depth from his music for my films. From my next film onwards, I wouldn't say a word to him to avoid confrontation. And since then, he wrote music for all my films with no exception. And I was never disappointed. Sometimes I spoke with his wife, as an intermediary but never directly. Sometimes it was my wife who was speaking with his wife. That was the way how we survived without confronting each other. But we were talking about theology, physics, and everything else but music. Well, unfortunately, he was working with other bigger directors than myself like Francis Ford Coppola (Bram Stoker’s Dracula), like Kiesolwski and Polansky and many others. And I reproached him and said you are my good friend. Why do you write such good music for my competitors? He simply answered “Makes good films as they do” and I will write you good music. So even this terrible answer didn't discourage me and our friendship survived.

Abraham: When you made your film Imperative, you had named the main character as Augustine. What percentage of the audiences you feel recognized the connection?