“A sound like a rumble from the core of the earth”

—Jessica (Tilda Swinton), a Scotswoman and a scientist, describing the sound that woke her up one day from slumber in Colombia, a sound that she wishes to identify and understand (words spoken in the early part of the film)

“Why are you crying, when they are not of your memories?”

—Jessica’s new-found acquaintance Hernan (the metaphoric “hard disk," as he describes himself”) says to her, after Jessica (the metaphoric “antenna”, in Hernan’s words) physically connects with Hernan by Jessica placing his palm on her arm (words spoken towards the end of the film)

Memoria is a film

that recalls Carlos Reygadas’ opening and closing sequences of his Silent Light (2007), approaching

metaphysical mysteries using sounds and visuals. It was not surprising for this

critic that Reygadas was one of the many thanked by the filmmakers in the film’s

credits. Memoria equally recalls

sequences from Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 film Solaris (Kris’ sequences on earth outside his home before

travelling into space and Kris viewing the liquid world of Solaris from his

spaceship window) and Stalker (the

child watching the glass tumbler moving off the table, aided by external

vibrations). Viewers, who found Silent

Light, Solaris and Stalker

boring, would find Memoria

exasperating with almost negligible spoken words compared to those films and

mysteries deliberately left partially explained. However, for a viewer who

loves the films of Reygadas and Tarkovsky—Memoria

would be a strangely rewarding and exhilarating experience to view, mixing

science and the history of Colombia, where director Weerasethakul detects

parallels in recent times with his native Thailand. Those parallels become more

apparent if the viewer has watched two of the director’s films Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

(2010) and Cemetery of Splendor (2018).

|

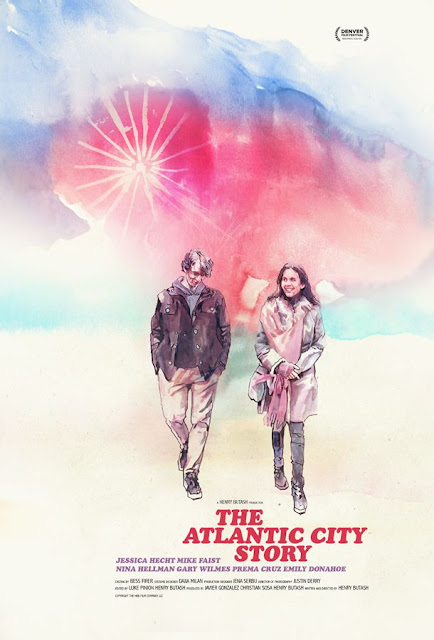

| Jessica (Tilda Swinton) becomes the antenna of "hard disk" Hernan (Elkin Diaz) by placing his palm on her hand |

|

| The archeologist Agnes (Jeanne Balibar) encourages Jessica to touch the manmade hole in the head of a skull of a girl who lived in Colombia 6000 years ago. |

Director Weerasethakul

had spent time in Colombia to research and grapple with the parallel histories

of Colombia and his native Thailand before he decided to write the original

script of Memoria as an extension of

ideas he had developed in his earlier films

Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives and Cemetery of Splendor. His fictional character Uncle Boonmee could

recall the past lives, so too in Memoria

can the mysterious elder Hernan, who claims he never left that village, as he

removes the scales of fishes to salt and dry them. In Memoria, there are several references to the dead being excavated in tunnels by road builders possibly referring to the dead bodies of the battles

between Marxist Leninist FARC activists and the Colombian militia as well as

the skeleton of a girl who had lived 6000 years ago in Colombia with a manmade hole

in her skull indicating the way she died. In Cemetery of Splendor, comatose

Thai soldiers were kept in hospital wards (over lands where Thai kings were

buried) with bright colorful lights to induce good dreams in the still alive

but comatose soldiers. None of these facts are mentioned in Memoria explicitly. It is left for an

intelligent filmgoer, familiar with the director’s past works to figure out why

Jessica’s eyes well with tears when she connects with “hard disk” Hernan, who

knows all the past lives of the people of Colombia.

|

| Jessica with young sound engineer Hernan (Juan Pablo Urrego),who was never real, presenting her the precise recorded sound |

Memoria is a film

on sleep, dreams, death and life. Jessica is woken from “sleep” by the strange

sound and is eager to know how the elder Hernan can “sleep” without memories

and watches him sleep for a while. Dreams play a part in the film as Jessica’s

sister Karen claims she was affected by a strange illness after she did not

feed and take care of a stray dog that had come to her doorstep. When Jessica

recounts the dog story back to Karen who has been cured of her illness she does

not recollect it. Who is dreaming--Jessica or Karen? The viewer learns from the

sparse conversations that dot the film that Jessica has lost her husband in the

recent past. Whose death certificate is Jessica asked to sign by Karen’s

partner? When Jessica connects with

“hard disk“ Hernan, Jessica’s ”antenna”

allows Jessica to “recognize” her past childhood items “visible” in the room.

However, earlier Jessica dreams that her dentist has died but her sister Karen

and her partner assure her that he is alive and well.

Memoria

communicates with its viewers using sound, silence and a visual magnetism rare

in cinema. That sound that Jessica and the viewer hears for the first time,

which is central to the film hits one after a long period of silence. That thud is recreated with amazing sound

engineering of the young Herman with inputs from Jessica and his studio

equipment. Later on in the film, Jessica and the viewer accost other denizens of the

same building where the sound engineer had worked who convince Jessica that no such

person as the young Hernan ever worked there or is known to them when Jessica

describes his physique. When Jessica hears the same sound on the street, one

Colombian, is startled and runs for his life while others are not affected. In

open areas in Colombia, the strange thud also scares a bird but no other human

seem to have heard it or is affected. The strange sound switches on a wave of

alarms in parked cars that subside as it started indicating it is not a human

action.

Jessica had come to Colombia to study the effect of a fungus

on orchids and eventually the strange sound opens her eyes to hidden histories

of the land and extra-terrestrial communication. When Jessica goes to a doctor

seeking a cure for her “affliction” by the strange sounds, she is refused

medication but instead advised to take an interest in either art or God to cure

her current state.

|

| The cinematography of Mukdeeprom, capturing still life, as in a painting, with birds in the far background, uninterested in the fish, even when the characters stop speaking |

|

| Jessica recalls objects in the room as parts of her childhood memory |

In Memoria, director and original scriptwriter Weerasethakul comes close to the world of Tarkovsky and the Polish science fiction writer Stanislaw Lem whose ideas were distilled in Solaris.

Weerasethakul is aided once again by

the cinematography of Sayembhu Mukdeeprom, who captures the beauty of Colombia’s

natural resources as though the scenes were still life paintings recalling the cinematography

in Terence Malick’s films: The Thin Red Line, Days of Heaven, and the bison

sequence in To the Wonder. Those who care to note the details of the

exterior sequence of Jessica and “hard disk” Hernan, will note crow-like birds

in the distance, birds that surprisingly do not seem to be attracted by the

fish being dried out in the sun. Therein lies clues to the film’s narrative

that unfolds in the last 15 minutes of the film.

Memoria, which won the Gold Hugo at the Chicago film festival, was given the following citation for the award: “.. for its sense of cinematic poetry and humanism. In this profound and meditative film, the director creates a story that emphasizes the connection people have to the places that they live, to the past and the present, and to the terrestrial and beyond. Tilda Swinton’s note perfect performance embodies Weerasethakul’s faith in cinema, in science, in secular mysticism, and in the possibilities of cross-cultural empathy and understanding.” The comprehensive citation captures it all. Memoria is a film that will exasperate many but be treasured by those who can pick up details in a reflective narrative and string them all together.

P.S. Memoria won the Jury Prize at Cannes film Festival in 2021 and the Gold Hugo for the Best Film at the Chicago film festival. Weerasethakul’s film Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010), Reygadas’ Silent Light (2007); Tarkovsky's Solaris (1972); and Malick’s The Thin Red Line (1998), Days of Heaven (1978), and To the Wonder (2012) have been reviewed earlier on this blog. (Click on the names of the films in this post script to access each of the reviews.) Memoria is one of the author's best films of 2021.