Rams is an unusual tale, remarkably told. Rams are male sheep and

the entire film is appropriately about two dour male, hairy, unshaven Icelandic

brothers.

The two male characters, Gummi and

Kiddi, are quite old and not married. They are not gay; they are not womanizers

either. They are both passionate sheep farmers, who live on different homesteads,

separated by a road and fences. It is indeed a strange tale to surface from a

matriarchal country, one of the only two such countries in Europe, the other

being Albania.

The tale, created by director Grímur

Hákonarson, is centred on the two brothers who have not talked to each other

for 40 years but communicate with each other by sending written messages

carried by a dutiful sheep dog. As you watch the film unspool, you wonder about

what could have led to the grim, silent antipathy of one brother towards

another. When the movie ends, you are never the wiser. But what one realizes at

that point is that this information really does not matter; the film is

actually about bonding and over-rides hatred. It is this that makes the film

remarkable.

|

| The hatred of Cain.. |

|

| ...changes under trying circumstances alone. |

Viewers learn from bits of

information that percolates. as the film progresses, that the deceased parents of the two brothers had made two interesting decisions. As most rational fathers would have done, the

father bequeathed his son Gummi the sheep he owned, because Gummi was obviously

the more dependable and better of his two sons in behaviour.

Now, since Iceland

is matriarchal, the mother of the two sons gets Gummi to promise that he would

let his undependable, wild and irresponsible younger brother Kiddi to farm

sheep as well.

|

| The reflection is more about sheep than about broken relationships within the family |

When the film begins both brothers are farming the best sheep in

the neighbourhood and are proud of their work. When one brother’s ram wins the

competition for the best ram, the other brother comes in second. They do know

the intricacies of sheep farming and are superior to the other sheep farmers in

their vicinity. They don’t have wives or children to bother about—their only

world is sheep farming. There is no clue provided within the film of the unknown events

40 years past that led to the break in aural communication between the two

brothers.

Hatred among siblings is unusually

common around us if we care to be observant.

Often this hatred is expressed through resounding “silence.” Even when

they hate each other, there is often a sibling bonding under the surface. When

one sibling in the movie is found by another drunk and freezing in the cold, he

is scooped up mechanically by a scooping truck operated by the other sibling and

dumped in front of a hospital without the sober brother getting off the truck—actions

that show both the contradictory feelings of an intense disdain as well as care

for the health of the other sibling, in a remarkable sequence where no words

are spoken. On another occasion, one sibling fires bullets at the other’s

house, smashing window panes. One hears the gunfire and the breaking of the

glass but no words!

|

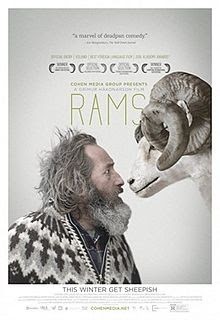

| Iconic shot of two rams--when the film Rams is about two hairy, stubborn men |

The strange reality is that such

animosity is not uncommon among siblings but ultimately blood is thicker than

water. The words spoken in the film by

one of the warring brothers underscore this oxymoronic situation “No sheep. Just the two of us.” The final

words spoken in the film “It will be all

right” have tended to confuse some viewers but if the movie is viewed

attentively there is no ambiguity. Perhaps the ambiguity stems from the fact

that the words are spoken by a sibling painted earlier in the film as being

wild and undependable. The ending of the film is not the film’s weakness; it is

its strength.

The message of the film goes

beyond sibling rivalry. Neighbouring countries go on long intense senseless wars

for similar unfathomable disputes and yet many inhabitants of these warring

nations like those of the other nation on personal terms. The message of Rams is not odd, it’s real. Only the

Cain and Abel tale often goes beyond siblings, in a modern, wider perspective.

|

| Nature and landscape of Iceland is a bleak backdop for the grim tale |

Grímur Hákonarson’s Rams has very little spoken dialogue,

often those are words spoken by tertiary characters whose dialogues flesh out

details about the primary duo. The elements of the film Rams that “speak” are the cinematography and the sounds of nature.

When icy winds blow in Rams, the

viewer shivers. It is little wonder that cinematographer Sturla Brandth Grøvlen (who

was also responsible for the single-take 2015 German feature film Victoria) won the Camerimage award for

this film. (One suspects that certain locations used in Rams were common with the 2015 Icelandic film Rúnar Rúnarsson’s Sparrows.) Director Hákonarson’s

choice of music by Atli Örvarsson is another element of the film that raises

its quality above the ordinary.

P.S. Rams is one of the author’s best 10 films of 2015. The film won the top award in the 2015 Cannes film

festival’s Un Certain Regard section, and major film awards at the Thessaloniki

(Greece), Hamptons (USA), Ljubljana (Slovenia), Palic (Serbia),

Transilvania (Romania), Valladolid (Spain), and Zurich (Switzerland) film festivals. It also won the Silver Frog

award at the Camerimage festival in Poland for its cinematography.