Several directors in Europe have in recent years made outstanding award-winning films on the subject of working class bread-winners losing their jobs and trying their best to claw back to a life of normalcy by finding another. The processes are devastating in each case. Foremost award-winning examples are Stephen Brize’s Measure of a Man (2015, France) and the Dardennes bothers’ Two Days, One Night (2014, Belgium). I, Daniel Blake continues to lead the viewer along the same paths of the films but with a difference—the film underscores the inhuman apathy of government employment systems for those suddenly forced out of work. All three films have a common thread—when you are out of work and cannot find another—a sudden camaraderie develops between the unemployed and others who have faced similar situations.

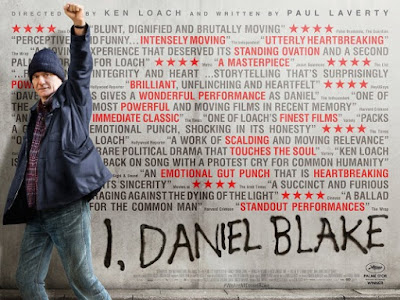

I, Daniel Blake is an outstanding film of 2016. It is a film that combines good direction (by

the 80 year old veteran filmmaker Ken Loach who returned from retirement to

make this film), a marvellous and credible screenplay by Paul Laverty (Loach’s

colleague for the past dozen films), good editing, and two very creditable performances by the main players. It is not surprising that the film was

bestowed the Golden Palm (Palme d'Or), the top honour at the year’s Cannes film festival, to

Loach for the second time in 10 years.

What makes I, Daniel Blake stand out among the three films is Paul Laverty’s

ability to infuse wry humour in the carefully chosen words spoken by its

characters. Words matter in this film. The film opens with a dark screen. Then you hear a telephone conversation –a

conversation between Daniel Blake, a 59-year-old carpenter who had a recent

heart attack or a cardiac event, resulting in a near fall while working on a scaffolding

and medically advised not to resume work, and an anonymous employee from the

British Department of Work and Pensions quizzing him about all his physical

conditions except his ailing heart condition only to file a report on Blake that

is obviously and quixotically incomplete and misleading. This conversation sets the mood of what follows—the

apathetic world of bureaucracy that does not believe in empathy for those

suffering from a medical condition that prohibits working in their chosen

trade.

The good carpenter is good with

his hands and quite literate. But he is not computer literate. The British

Department of Work and Pensions works on-line, on telephone, and very rarely

face to face. How does Laverty put it into

words? Here is a fine example. The British Department staff tells Blake “We are digital by default.” Blake, who

has had a rough time posting his applications on-line answers the bureaucrat

sardonically, “I am a pencil by default.”

Carpenters work considerably with pencils. This is not flowery writing—the

script is socially loaded beyond the obvious repartee.

The audience can only agree with

Laverty and Loach when Blake calls the Department a “monumental farce.” One is reminded of the Cuban masterpiece Death of a Bureaucrat (1966) directed by Tomas Gutierrez Alea, in which a widow of a dead bureaucrat cannot access her widow’s pension and

benefits because a critical identity card was buried with her husband’s body in

the coffin and the Communist bureaucrats refuse to process her benefits without

it.

Both Laverty and Loach teams up

film after film to present us individuals who struggle to survive in a social

world that sweeps them away because of incidents that they cannot control or

intended to face. The Cannes’ Palme d’Or winner The Wind that Shakes the Barley (2006) where the main character

joins the IRA after he clearly made up his mind not to do that after witnessing

a life changing incident involving British troops or the comedy The Angels’ Share (2012) where a young Glaswegian

narrowly escapes prison sentencing and subsequent troubles by a chance visit to

a Scotch whisky distillery which ultimately leads to a well paid permanent job.

In Tickets (2005), a group of well-meaning

football-crazy Glaswegians on a train journey in Europe find one of them have

lost their ticket, possibly stolen and suddenly have to grapple with future consequences

of that situation that makes them more socially responsible. The dozen films of Loach and Laverty build on Loach’s

Kes (1969) written not by Laverty

but by a book by Barry Hines, where a young middle class school kid, given

little sympathy at home and in school takes interest in training a pet kestrel

by reading a book that he steals from a bookstore. Pre-Laverty and with Laverty, Loach has dealt

with characters whose lives change by events that were not planned.

What Laverty brought on Loach’s

table was spoken language that seemed to have a visual power beyond that of the

camera. “A pencil by default” is not something that you capture by the

camera; the viewer has to figure out the connection between a pencil and the

world of the carpenter. Apparently the film's script was prepared with help on inputs from real jobless urban poor who had to seek financial and food assistance in the UK and their experiences. The brilliance of Laverty’s screenplay writing comes

towards the end of the film, when the curriculum vitae that he was forced to

learn to write for getting a Job-Seekers’ Allowance is read out at his “pauper’s

funeral.” What is read out, are words

that we never could have guessed were written on the pieces of paper Blake was

handing out to prospective employers. And at least one did respond

positively. What is written by Blake is

Laverty’s magic that no camera could have captured. Daniel Blake is, as stated in

his own words in his CV read out at his funeral “a citizen—nothing more,

nothing less.”

I, Daniel Blake does not belong exclusively to director Loach and scriptwriter

Laverty. It belongs to two other talented individuals chosen by Loach—actor Dave

Johns who plays the character Daniel Blake and actress Hayley Squires who plays

who plays Katie, who accidently crosses the path of Daniel at the British

Department of Work and Pensions facilities. Now Katie is single mother of two

kids. She has been uprooted from London to Daniel’s town and arrives at the

office late because she boarded the wrong bus. Laverty’s magic allows both

these two wonderful human beings to meet when there being knocked around by the

unfeeling bureaucrats, by a "Laverty" accident. It is not surprising that Ms Squires has been nominated

for a BAFTA award but it is surprising that Dave Jones has not been nominated

for the restrained power of the performance, his first in a feature film. But

then one needs to congratulate Loach for picking these two main actors.

Director Loach has a team that he

works with on his recent films beyond the talented Laverty. A major team member is film editor

Jonathan Morris who has worked with Loach longer than Laverty. The editing in I, Daniel Blake, does not grab your attention until the ultimate “pauper’s

funeral.” Another member of the Loach

team is the cinematographer Robbie Ryan who worked on the three last Loach

films I, Daniel Blake, Jimmy’s Hall,

and The Angels’ Share. It only shows

that the Loach team has constantly evolved but the best of them tried and tested stay with

Loach.

I, Daniel Blake is undoubtedly the best work of Loach and deserved the Cannes honor.

I, Daniel Blake is undoubtedly the best work of Loach and deserved the Cannes honor.

P.S. I, Daniel Blake and Paradise are two outstanding

works included in the author’s top 10 films of 2016. Loach’s The Angel’s Share (2012) and Tickets (2005) were reviewed earlier on this blog and the former is one of the author’s top 10 films of 2012. Two other films mentioned in this review The Measure of a Man (2015, France) and Two Days,One Night (2014, Belgium) were also reviewed

earlier on this blog.

No comments :

Post a Comment